A shark and ray die-off in the San Francisco Bay that peaked in April and May has dwindled in the last few months, and the zig-zagging hunt for an explanation has neared at least a partial solution to the mystery.

“We’re much further along than we were a year ago,” says Mark Okihiro, a California Department of Fish and Wildlife senior fish pathologist who has led the state’s investigation. “Certainly even further than we were just a few months ago. But the story has changed quite a bit since [the spring].”

The die-off appeared to be centered on the shoreline around Foster City. Stranding reports came from nearly every part of the Bay, however, and involved several fish species. In an email update from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife on July 21, Okihiro estimated the die-off has claimed more than 1,000 leopard sharks, 200-500 bat rays, hundreds of striped bass, and nearly 50 smoothhound sharks, as well as small numbers of thornback rays, guitarfish, and halibut.

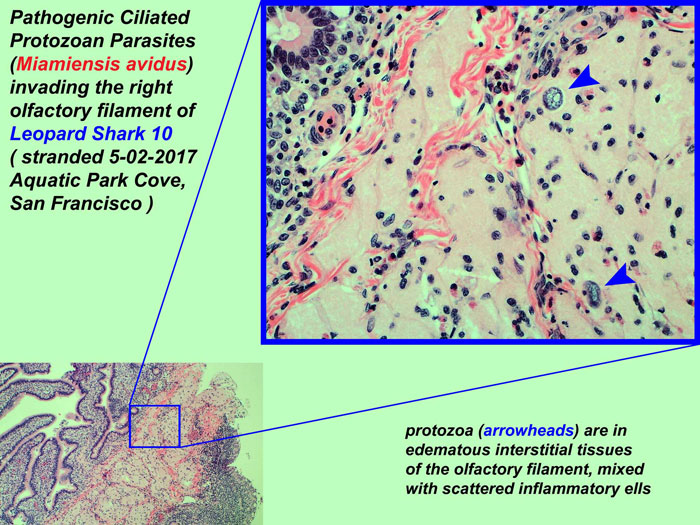

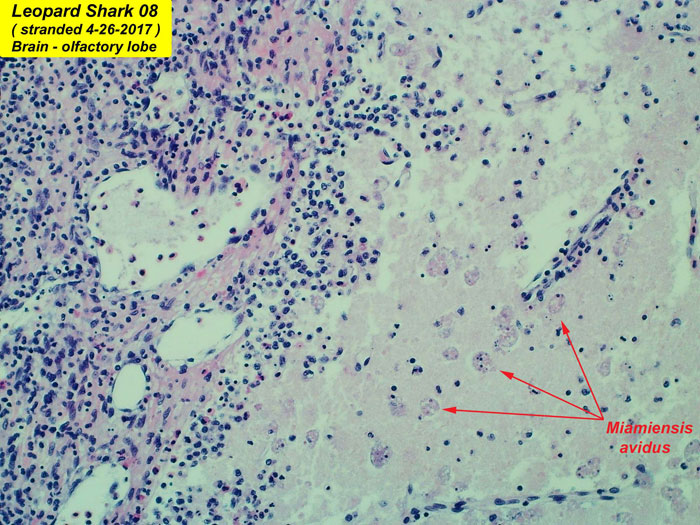

Most of those deaths, or at least all of the several dozen Okihiro has been able to investigate, resulted from brain infections. Something is invading Bay fish, moving into their brains, and eating away, causing the fish to become disoriented and eventually to die or strand. Okihiro originally thought the cause might be a fungal pathogen that he found growing on Petri dishes cultured from the brain and inner ear fluid of the first three leopard sharks he examined. By early May, after examining a handful of sharks he’d gathered while walking the beach south of the San Mateo Bridge, Okihiro thought he was closing in on a fungal killer.

“[The explanation] looked really good for the first two or three sharks,” he says. “It’s a good example of why you can’t, or at least you’re not supposed to, rush off when you have preliminary data.”

The shark body count mounted through mid-May, but Okihiro stopped seeing fungi growing on his agar plates. As he cast around for explanations, he returned to something he’d seen while inspecting white seabass hatcheries in Southern California. Last year, older white seabass in the hatchery started growing disoriented and eventually dying. When Okihiro examined them, he found lesions in their noses, and in the fronts of their brains. Looking closely, he found evidence of a virulent fish-brain-eating protozoan parasite called Miamiensis avidus.

Protozoan pathogens had occurred to Okihiro to explain previous mass shark die-offs in the Bay in 2006 and 2011 — but he’d dismissed them. He looked closely in 2011, but the parasites weren’t easy to find in the brains of sharks he was dissecting. He knew that in white seabass, when the protozoans were there, you couldn’t miss them. So this year when the sharks started washing up dead, he first looked for other explanations: viral or bacterial pathogens, or exposure to contaminants in the water.

When he still couldn’t find a consistent answer this spring, though, Okihiro went back and reconsidered Miamiensis avidus. This time, once he was really looking he found evidence of it everywhere. He saw it in the location of the lesions in the sharks he dissected. He could see the protozoans themselves, circular hairy blotches infesting the fixed tissue samples he’d taken. Finally he sent samples of cerebrospinal fluid to the UCSF lab of Joseph DeRisi, an expert in the genetics of infectious disease. Hanna Retallack, a graduate student in DeRisi’s lab, used techniques called polymerase chain reaction (or PCR) and metagenomic next generation sequencing (or mNGS) to look for genetic evidence of Miamiensis avidus infection. She found the protozoan’s DNA in 14 sharks, and its RNA signature in five more samples. Okihiro now says he’s “90-100 percent confident” the protozoan pathogen is the primary cause of the strandings.

“So we were on the right track 11 years ago,” Okihiro says. “It just took us a while to get back to it.”

If Miamiensis avidus is to blame, though, there’s still the question of why this year, and why it got so bad. The protozoa is a common parasite in fish, affecting a wide variety of species. It’s probably present and well-adapted to some kind of fish that already lives in the Bay, Okhiro says, perhaps a rockfish or perch species. What caused it to affect sharks so particularly in 2006, 2011, and 2017? What was different this year?

If you lived through the Bay Area winter this year, you may guess at the answer: it rained a lot this year. It also rained a lot in 2011, and 2006. That much rain adds at least two more variables to the mix. There was a huge freshwater surge into the Bay that lowered the salinity of the water, particularly in the slow-circulating South Bay. Warner Chabot, the executive director at the San Francisco Estuary Institute, suggested in an email to reporters and conservation groups that salinity levels were as low in the South Bay this year as they’ve been in decades. Low salinity might have weakened the sharks’ immune systems, causing the parasite to take hold with greater ferocity than normal. “The 2017 low salinity anomaly may have increased the stress on leopard sharks,” Chabot wrote, “and should be considered as a factor for this year’s dramatic decline.”

It’s not just low salinity, though. All that runoff contributes huge influxes of human pollutants into the Bay: personal care products, pesticides, motor oil, heavy metals. Leopard sharks gather in large numbers and swim into shallower, more stagnant water in the spring, just as those contaminants are flushed in.

But if the die-off did have something to do with salinity or contaminant exposure, it’ll be hard to tell. A California Department of Fish and Wildlife press statement in late May concluded that in either case, it “will be largely beyond our ability alone to address.” It turns out that there are a number of unanswered questions about even the charismatic big predators in our densely populated urban estuary, and not much funding out there to answer them.

Which is why this is such an odd mystery. These are sharks that are dying, after all. They have their own week on the Discovery Channel. They’ve made five Sharknado movies. And yet talk to a shark researcher and they’ll point out: sharks might be popular, but research into them generally isn’t funded accordingly. Okihiro’s main job is to inspect white seabass hatcheries in Southern California; he’s the statewide lead on shark strandings because there’s overlap between the diseases that infect the seabass and the diseases that infect the sharks. Yet to sort out the complex dance of contaminants, environmental conditions, behavior, biology, and pathogens that killed these sharks might take dozens of researchers attacking the problem, and funding to match.

“The problem is, every researcher would like more funding,” Okihiro says. “The drought has chewed up a huge part of the Fish and Wildlife budget. It’s the same with CalFire, where wildfires just chew up a huge amount of the budget so there’s very little left to the pie to slice up for other projects. I’m appreciative that there’s more interest, and Fish and Wildlife has recognized that this is a serious problem that needs looking at. But right now I think we’ll have to try and let the dust settle and see what we would like to do going forward.”

If you see a stranded or dying shark anywhere in California, call or text the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s CalTIP hotline. You can also report strandings to the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation. Or take a picture and upload it to iNaturalist, where it can be added to a project tracking leopard sharks and bat rays around the Bay.