I’ve walked along Limantour Beach in the Point Reyes National Seashore dozens of times over the years, but never seen anything like the small jelly pods I found scattered in the sand along the tidal line on a walk this fall. Clear, translucent, and the size of a thumb, I suspected they were jellyfish that had washed up with the tide — but a closer look revealed something far more unusual.

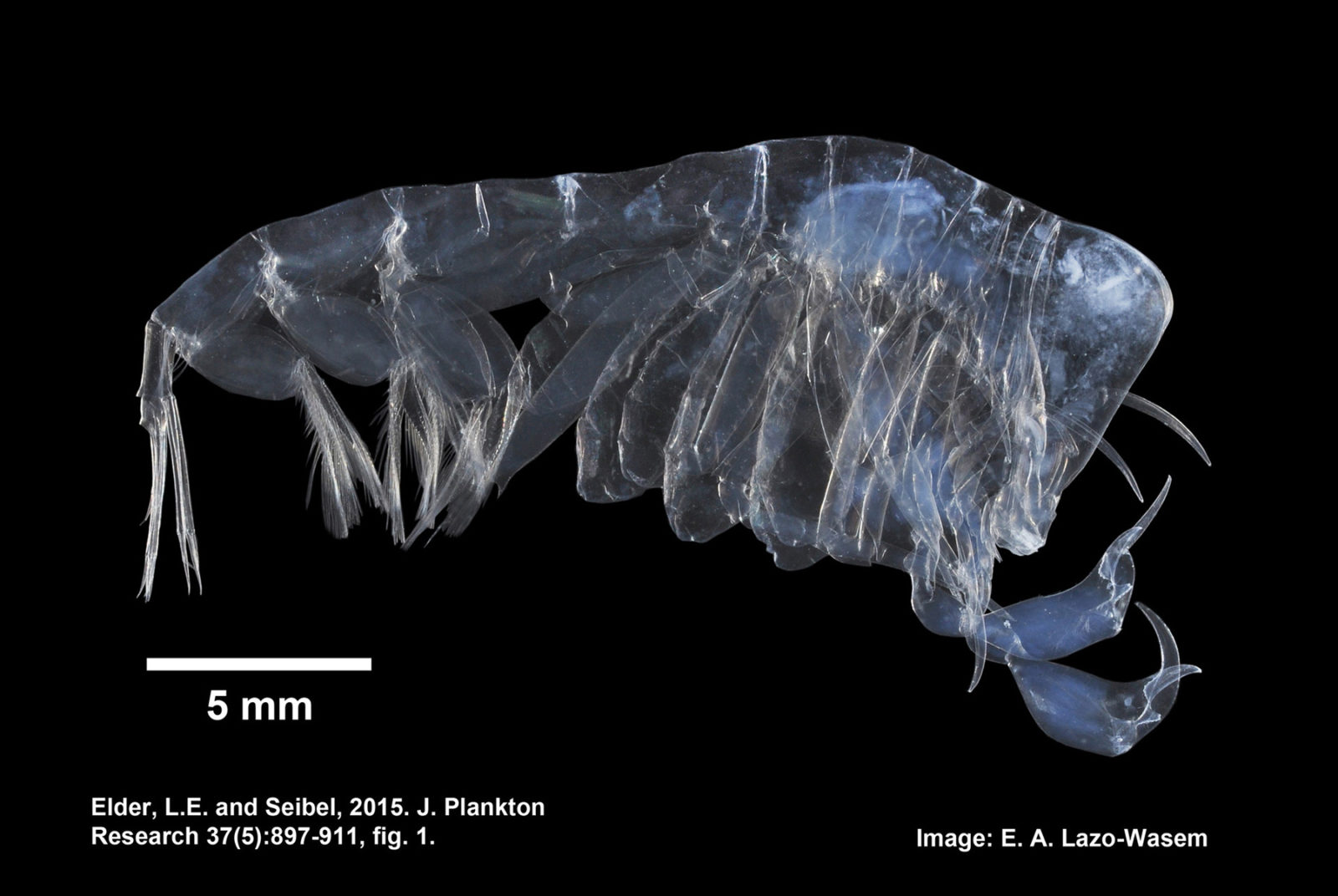

Holding one in my hand, I could see that it was hollow inside, with an even smaller creature curled up in the cavity. It looked clear, matching the jelly pod around it, but also somewhat like a crustacean. I thought of a shrimp, but that didn’t quite match. And then, as I puzzled over it, the mystery creature reached out of the pod with a tiny little arm and an even more miniscule pincher at the end, not unlike a lobster claw. With four eyes looking back at me from a translucent, bulbous head, it looked like an alien from a movie set.

When I got home I turned to the Internet for answers, typing “creature from the movie Alien” into Google. To my surprise, this worked. The search helped me identify the creature as Phronima sedentaria, and at least some sources said the tiny ocean animals served as inspiration for the terrifying monster in the movie Alien.

The little jelly barrels I found on the beach were salps, a type of common oceanic zooplankton. Phronima catch them and use their tiny claws to dig out the center — consuming what it removes — and then crawl inside of their new floating home.

Like the salps they parasitize, Phronima are another type of zooplankton, demonstrating the range of organisms in this group, which stems from the Greek for “drifting animals.” While salps are more similar to jellyfish, Phronima are crustaceans, like lobsters and crabs. They belong to a family of marine crustaceans known as Hyperiid amphipods, which specialize in parasitizing salps and jellies.

Karen Osborn, a researcher at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, says Phronima are actually engineering their hosts. “They don’t just hollow out the salp and use it, they actually have glands and they secrete material onto it to kind of restructure it,” she says. “So the salp barrel that they live in is shaped quite differently from the salp itself, and it’s also much tougher than the salp tunic just on its own, which is pretty floppy.”

Katie O’Dwyer, a parasite ecologist at the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology in Ireland, first encountered Phronima in 2011 when curious citizens sent her samples found on beaches from the west coast of Ireland. She found them herself a couple of years later on a beach in New Zealand, prompting her to write the article that helped me identify the species.

According to O’Dwyer, the salp home helps Phronima to be more buoyant in the water. Interestingly, she says it is unclear whether the salp is killed when parasitized by a Phronima. “A strange finding I have come across is that the cells in the salp casing have been shown to still be alive,” she says. “I guess this brings up some questions about what it means to be alive as a salp!”

This is particularly surprising given the following description from Observations on the Anatomy and Behavior of Phronima sedentaria: “The female entered the salp, cut out the brain and gill bar, and consumed them, ate the stomach and its contents… cutting off strips of tissue at both ends, and removing pieces of the internal organs…”

Photos of Phronima peering out through the glassy walls of a salp give the impression of a womb, and that isn’t far from the truth. Females use the salps as floating nurseries for their young to develop, laying hundreds of eggs that align themselves inside the barrel, a behavior that led to their common name, pram shrimp. When they swim, Phronima look like a kid learning to swim with a kickboard, holding their front legs and body inside of the barrel while kicking and propelling with the smaller legs along their tail.

Osborn studies the evolution of eyes in Hyperiid amphipods, which she says have “incredible compound eyes, very different from all the other compound eyes that are known, even on land or the sea.” She told me that Phronima actually have two sets of eyes that take up nearly the entire head. The two round, dark-red retinas at the side of their face supply nearly 180-degree peripheral vision. More surprisingly, the pyramid-shaped retinas in the center of their face are connected to the large bulge at the top of the head, the one that gives Phronima such an alien appearance. This is another set of compound eyes, similar to a fly’s, with several hundred lenses that allow it to see directly overhead. All of these eyes give Phronima a visual advantage in the dark, blue light of the sea.

Phronima are common off the coast of California, the researchers said. They occur in open ocean and coastal waters, anywhere from 200 to 1,100 meters deep, and migrate toward the surface at night. Most zooplankton take part in this nightly migration, which allows them to access the more nutrient-rich waters near the surface, sinking to darker depths to avoid predation during the day. Their drifting nature subjects them to ocean currents that occasionally wash them ashore, where they can live for several hours before drying out.

Despite their abundance in the vast ocean, it would be difficult to seek them out. The precise conditions that lead to the beaching of their salp hosts have not been studied, and it is impossible to say how many salps would need to be examined before finding one inhabited by a Phronima. A look at the citizen scientist app iNaturalist shows that there have been just 33 observations recorded, including one other from Limantour Beach. The records span temperate waters around the world, including North America, Europe, Japan, and New Zealand.

According to Osborn, they are tough little animals, making them rather easy to study in a lab setting because they can survive in a tank for weeks at a time. “They’re pretty nasty creatures actually, when we collect them, we have to keep them all in separate containers because they eat everything else that’s around them, like other Hyperiids, other Phronima, other jellies, whatever they catch they eat it pretty quickly.”

She says that although the origin of the anecdote is unknown, the similarities between Phronima and the Alien Queen are striking — she once led a student exercise that compared imaginary creatures to real animals, and “we included Phronima in there, but instead of a picture we had a video of them moving around inside their barrel and the clip of Alien that we had was of it moving around in a hallway, and it was so similar, it was really a bit freaky.”

With their mysterious deep-sea lives, unnerving appearance, and parasitic behavior, their enduring association with aliens doesn’t seem misplaced. It is fitting that the name Phronima stems from the Greek for clever.