Amid the din of humming electric motors and gurgling laboratory aquarium tanks, life, new and precious, has been born.

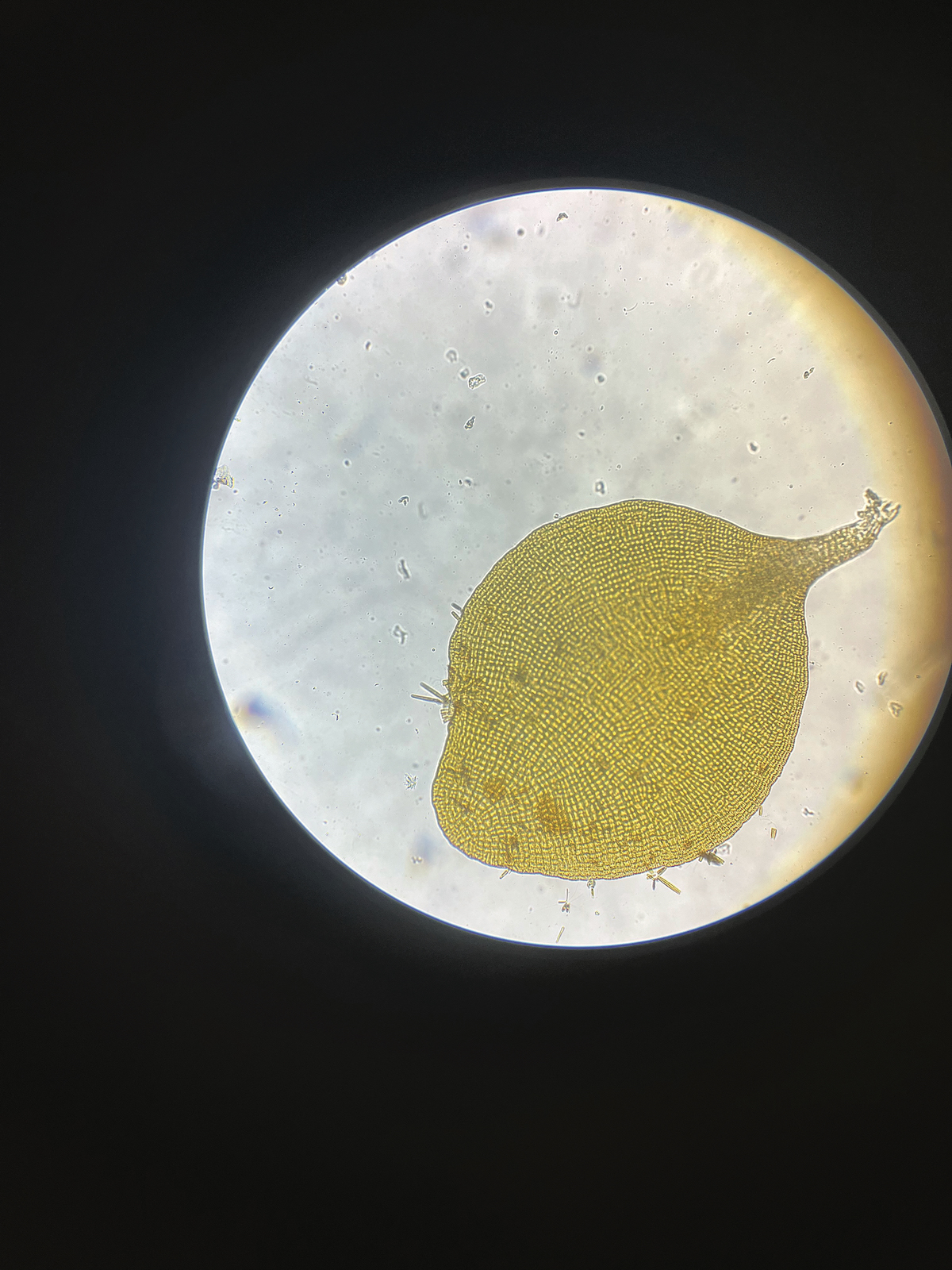

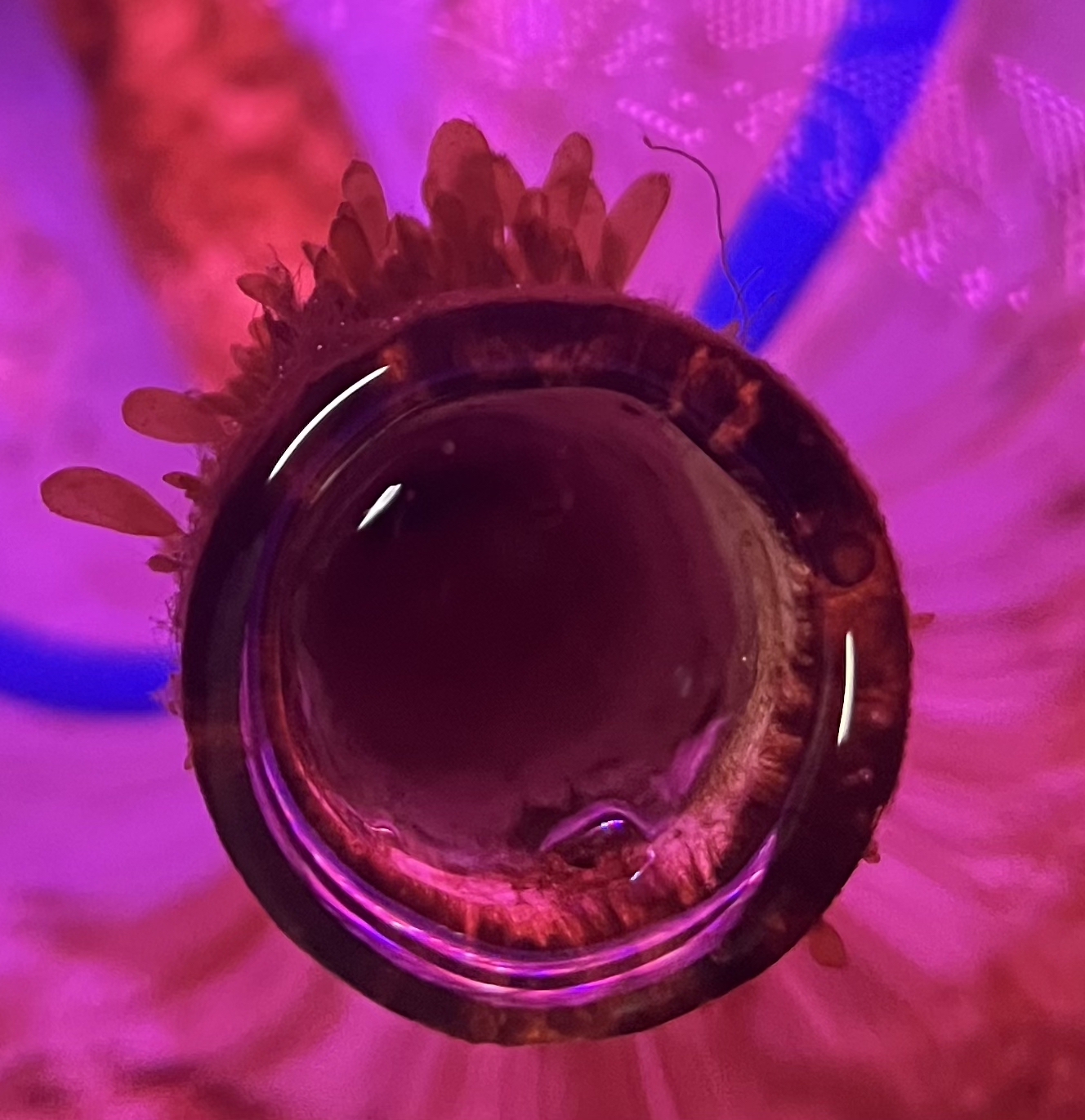

“Aren’t they so cute?” says Rachael Karm, a Sonoma State University research technician, who’s peering into an open-topped tub of swirling seawater, alongside researchers Julieta Gómez and Rietta Hohman, of the Greater Farallones Association. The objects of their admiration are tiny, brown algal sprouts clinging to submerged PVC pipes, illuminated by Barbie-pink grow lights. They look about as consequential as the scum in a dirty fish tank. But these little babies—two-month-old sporophytes of bull kelp, Nereocystis luetkeana—could represent the future of Northern California’s imperiled kelp forests.

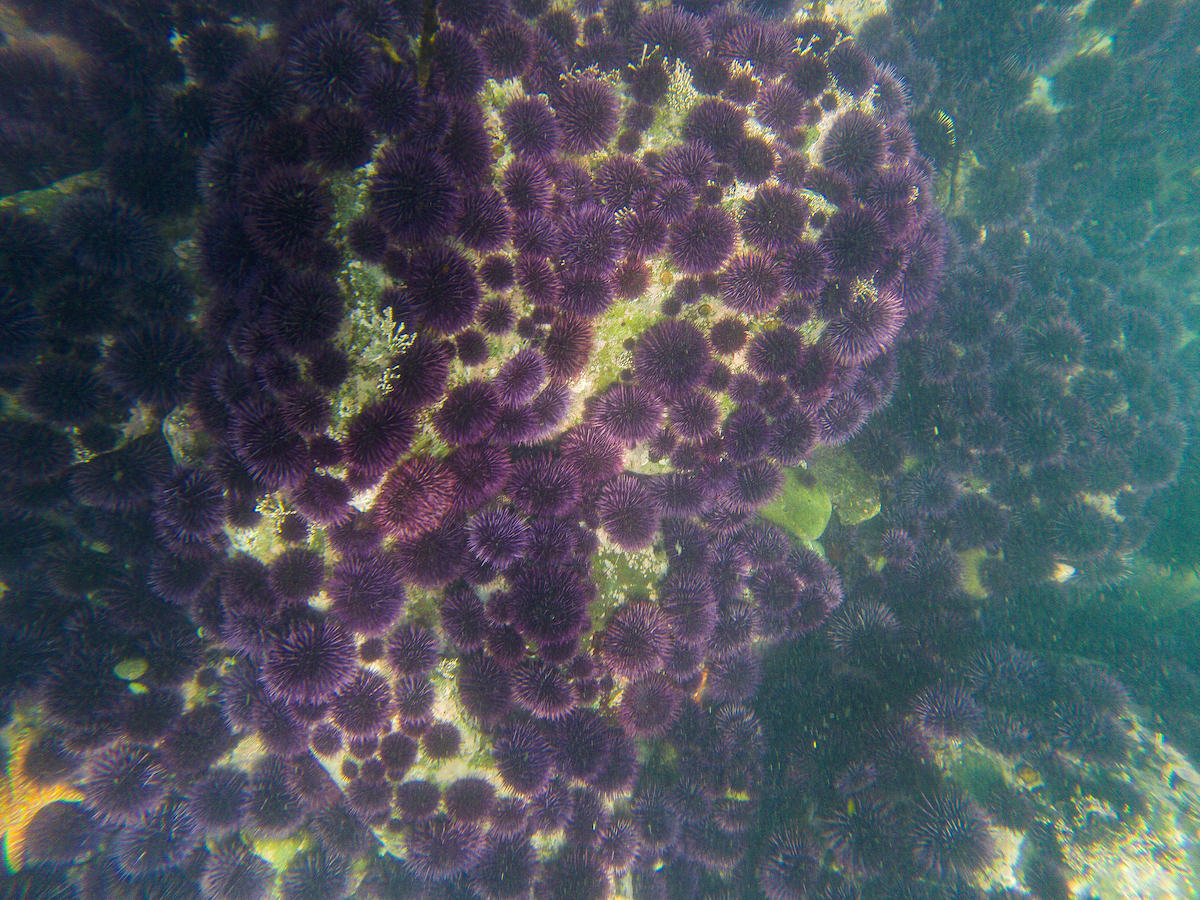

At about three months of age, these youngsters will be transferred from the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory and outplanted at two open-ocean sites along the Sonoma County coast, where extensive kelp forests collapsed a decade ago. Today, the North Coast’s rocky seafloor is carpeted with “barrens” of purple sea urchins that have mowed down nearly every last stalk of kelp. Researchers hope these sites will be the starting point for a full-fledged kelp comeback—an outcome that has so far eluded other bull kelp restoration projects.

This story is the second in Wild Billions, a series in which Bay Nature is examining the impacts of—and obstacles to— potentially transformative federal funding for nature in the Bay Area. Read more: Historic Money for Bay Area Nature Has Started to Flow. The Challenge? Spending it.

Send a tip, or feedback: wildbillions@baynature.org

A fresh flush of funding could help. The Department of Commerce, via the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has awarded $4.9 million in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law money to the nonprofit Greater Farallones Association to restore kelp forest habitat in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. That’s landing on top of $4 million from other federal and state sources. The project, which began in 2017 and started on-the-ground restoration in 2022, will continue for at least four years.

Directing the effort is Hohman, the Greater Farallones Association’s kelp restoration manager, who acknowledges the steep climb ahead. This restoration effort is “not going to flip the entire Northern California coastline from urchin barren to kelp forest,” she says.

“What we’re really focused on is finding these areas that have the highest restoration potential,” she says, “and focusing our efforts on those specific spots.” The goal is to create refugia of kelp—oases, and spore banks, that could seed a broader rebound.

If the current desertlike seascape can be reverted into something akin to a rainforest, bull kelp will be its foundation—the canopy. Underneath its languid stalks, stretching 30 to 60 feet from the seafloor to the surface, a diverse understory of smaller algae will sprout like shrubs and ferns. Among these will teem invertebrates and fishes, like abalone, lingcod, and cabezon, each occupying its own ecological niche. That’s the dream.

Sitrep: dire

But Northern California’s bull kelp may never fully recover. Its crisis began in 2013, when a mysterious wasting disease wiped out the sunflower sea star, which kept purple urchins in check—just when a two-year spell of unusually warm ocean water killed a great deal of bull kelp. The urchins took over, and the impacts are still rippling through the ecosystem. Once-abundant bottom-dwelling and schooling rockfishes have vacated parts of the nearshore zone—as I’ve noticed over 15 years of regularly diving here. Red abalone, also kelp foragers, have starved en masse, leading to a total ban on harvest. Red sea urchins, a different species than the purples, are also out of an important food source. Though they haven’t died off, their valuable golden gonads—called uni in culinary settings—have shriveled to almost nothing, making them worthless to commercial divers. The more numerous purples are persisting in a similar zombie-like state. And they have grown brazen. Whereas in a healthy kelp ecosystem, these spiny echinoderms would hide in crevices, eating whatever tidbits of kelp drifted down their way—in the predator-free barrens they go everywhere they please, ready to mow down any kelp that might sprout.

The dramatic relationship between lush kelp forests and bleak urchin barrens is a textbook example of a phenomenon ecologists call “alternative stable states,” in which two very different ecosystems can exist in the same place, under the same environmental conditions. Urchin barrens are extremely stable, and generally almost impervious to human efforts to flip them back into a kelp-dominated state. Part of this resilience comes from the incredible durability of individual sea urchins: Even after they’ve eaten through their own food supply, they can live in a semi-starvation mode for many years—decades, according to some reports.

Alternative stable states can flip from one to the other when some powerful, temporary disturbance rocks the ecosystem. In the few cases in which people have transformed urchin barrens back into kelp forest, they have done so mainly by removing a massive quantity of urchins.

But there is a more pessimistic possibility as well: that ocean conditions—especially temperatures—have fundamentally changed to the point where the urchin barrens represent not an alternative stable state, but a whole new ecological regime. Elsewhere in the world, including Hokkaido, southeastern Australia, and the Aleutian Islands, urchin barrens have lasted decades after they replaced kelp forests. In parts of northern Europe, ocean warming is expected to locally extirpate the keystone kelp Laminaria digitata. One study found that overall, kelp forests are declining in more regions than they are expanding. Relief is nowhere in sight, as ocean waters worldwide have warmed to record highs in 2023.

“Climate change is making the transition from kelp forest to urchin barren easier than the transition from urchin barren to kelp forest,” says Jorge Arroyo-Esquivel, a postdoctoral fellow at the Carnegie Science Center in Palo Alto who has studied kelp ecosystem restoration.

Kelp biologist Dan Reed, at UC Santa Barbara, who is not involved with the Sonoma project, thinks that if global warming is the main culprit, saving kelp could eventually be a lost cause.

“If that’s the concern, it’s not just kelp,” he says. “It’s the whole world that’s suffering.”

The urchin battle has begun

Whatever dynamic is at play, everyone seems to agree: The urchins have got to go. People have already spent an enormous amount of effort on this goal along the North Coast. Since 2018, volunteer divers have smashed untold thousands of urchins in place with hammers or rocks (a method scorned by some scientists, who worry it could affect fishes’ feeding behavior, damage the seafloor, or produce clouds of viable urchin gametes that pump up the urchins’ numbers even more). Other efforts have focused on removing urchins from the water.

Tristin Anoush McHugh, kelp project director with The Nature Conservancy—one of two dozen groups and agencies partnering on the new effort—says prior work has led to “a response of kelp” at some sites but not a full-fledged bull kelp recovery. She attributes this to a lack of funding preventing a full-scale execution of the idea. But they’re refining their approach. At a site near Albion, she says, “we’re doing targeted urchin removal with commercial divers twice a month, consistently, all year.” She’s among those hoping the kelp outplantings will accelerate recovery.

The plan in detail

Before the kelp babies arrive at Fort Ross and Timber Cove, they’ll need a properly prepared nursery—meaning one without so many kelp-eating urchins. The game plan is to hire divers to manually remove urchins from several acres of rocky seafloor. (They’ll be composted on land.) Then, culling will continue as kelp outplanting begins, in 200-foot quadrats, with three different methods. Hohman and her team, in scuba gear, will drill bolts into the rock and run sturdy lines between them that are studded with juvenile kelp starts. The biologists will also glue small paver stones bearing kelp sprigs to the reef. And they will sink some mesh bags inoculated with kelp spores. By diving and with overhead drones, the team will monitor the new kelp beds to see which method works the best.

The hope is that the kelp takes and grows, and holds steady against the urchin armies bristling around it. Once the sporophytes are mature, at several months of age, they must also successfully reproduce, by releasing spores from irregular blotches, called sori, on the ends of their blades.

While the kelp “clotheslines” will be elevated about a meter off the seafloor to keep them safe from hungry urchins, the next generation of kelp, the scientists hope, will grow from the seafloor itself. Eventually, they plan to scale up the plantings to 27 acres across three sites.

Getting lucky would help

In the best of scenarios, the kelp will establish oases and even gain momentum, pushing through the urchin barrens, as Matthew Edwards, a kelp system expert at San Diego State University who is unaffiliated with the Greater Farallones Association’s project, describes. “Now, suddenly, you don’t need to put out lines of sporophytes, you don’t need to put out [inoculated] boulders,” he says. “You just need to get rid of urchins. … It’s really incremental, but if you get these kelp beds restored along the coast, they will start to slowly expand, I think.” Urchin removals would get easier, “and at some point those patches are no longer small patches—they’re forests again.” The kelp could perhaps even reclaim the coast.

Marissa Baskett, a UC Davis conservation ecologist who studies kelp forest dynamics, says that restored kelp groves could rain bits of drift kelp down on the urchin masses—lulling them back to bed and allowing new kelp stalks to sprout. But she says it seems just as likely that “without constant management intervention” by divers, the urchins would simply eat the adult kelp. And manually removing urchins, planting kelp, and guarding it from grazers is an incredibly labor-intensive, and expensive, prospect.

Kelp will probably only spread widely if the scientists get lucky—if, say, some outside environmental force, like predators or disease, piles on and helps kill urchins on a regional scale. Urchins do undergo boom-and-bust cycles, and the North Coast ones are already starving, having eaten all the kelp. But no one can say when the bust will come.

Until that happens, Hohman and her collaborators hope the restored kelp patches will survive as spore banks—ready to spark a recovery when conditions allow.

No guarantees

Most kelp experts Bay Nature interviewed agree the project is worth a shot, especially the urchin removals. Edwards’ own research has suggested that the supply of kelp spores in the wild “is not huge,” so supplementing them may well speed restoration. He wonders, though, whether the sporophyte clotheslines might be too delicate for the North Coast’s rough waters.

Reed, at UC Santa Barbara, thinks a simpler cull-and-wait approach could work. In 1999, he helped conduct an effort to plant giant kelp beds on an artificial reef in Southern California. Hundreds of kelp transplants, he says, were “totally swamped out by natural recruitment,” apparently from kelp groves two miles away. While kelp patches are few and far between on the North Coast, Reed suspects enough kelp remains to repopulate the area. In support of his theory, bull kelp did rebound for a hot second in the summer of 2021, though it died off again. “That money might be better spent just killing urchins,” he says of the outplantings.

If the kelp doesn’t take, Hohman says, the experiment will still be valuable. “Even with failure, we still learn,” she says. And McHugh, at The Nature Conservancy, agrees, noting that even then, a wide range of other seaweeds could still benefit from the removal of urchins, which eat all sorts of algae.

“We’re trying to restore an ecosystem, not just bull kelp,” she says.

Wanted: hungry, hungry helpers

Facing a never-ending marine gardening project, many biologists are seeking a respite from their toils—by reintroducing an urchin predator.

One such candidate is the sunflower sea star, which researchers in Washington are studying with the hope of breeding and releasing it back into the wild. Just the presence of these predators is known to send purple urchins scurrying for cover. In underwater time-lapse footage, three-foot-wide sea stars—clearly, masters of the uni-verse—dance, glide, and spin their way over the rocky seafloor like giant Roombas, mopping up smaller creatures in their paths as others flee.

Another option is the southern sea otter, which can eat urchins in astonishing quantities. Otters were wiped out from much of their West Coast range by fur hunters in the 19th century, but where they do still exist—on California’s central coast and in Canadian and Alaskan waters—they are a keystone species that helps maintain kelp forests. That’s part of the reason that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering a reintroduction program north of the Golden Gate. In June, agency biologists toured the coast with placards and displays, promoting the concept. Either predator could help control the urchins-gone-wild—both by eating them and by scaring them back into hiding.

Going all in

The Greater Farallones Association project is an attempt at what restoration scientists call the “Field of Dreams” approach. Build the kelp forest, and the fish—and everything else—will come. As long as you don’t half-ass it. You have to plant the kelp densely enough that it can really take over—and you have to get rid of enough urchins to give the kelp a fighting chance. Arroyo-Esquivel and Baskett published research in March that used statistical population modeling to show how a small-scale version of this strategy could snowball and push through the urchin barrens. That’s the holy grail of kelp restoration—initiating a natural flip from urchin barrens to kelp forest. That is what the Greater Farallones Association is trying to achieve by laboriously planting and protecting kelp sporophytes all summer.

“You don’t want to be restoring habitat forever and ever,” Hohman says. “You want to restore the habitat and then move on.”

But in a changing world, this could be a long shot. And some, like McHugh, suspect people may need to steward the kelp indefinitely for it to survive. Even if a predator is reintroduced. Even if urchin densities are more balanced with kelp. “I don’t think there’s going to be a world where we can fully step away,” she says.

Support for this article was provided by the March Conservation Fund.