In a small kitchen inside the Monterey Bay Aquarium, senior sea otter rehabilitation specialist Allie Bondi-Taylor prepares a baby bottle of clam-flavored milk formula, and then slips a black face shield and long gown over her clothes. It’s what aquarium staffers call the “Darth Vader” suit. The hungry baby otter in the next room is not allowed even to see a human face, lest he imprint upon his caregiver, or learn to associate humans or their forms, smells or sounds with food.

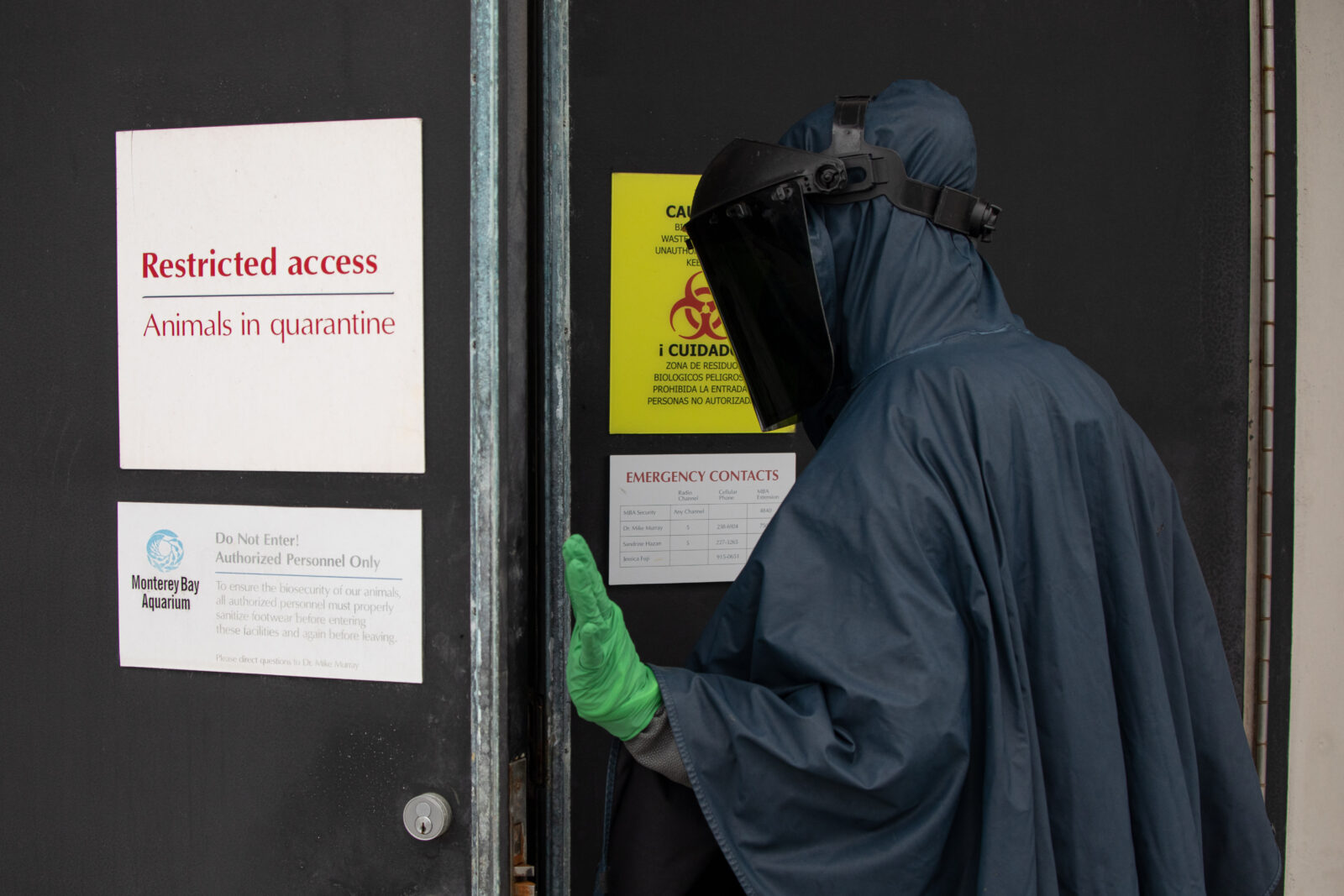

Identity concealed and baby bottle in hand, Bondi-Taylor enters through a door marked “Restricted Access.” On the other side of the wall, in a room adorned with sea otter mementos, a few aquarium staff and volunteers huddle around a monitor, watching as Bondi-Taylor scoops up a two-week-old sea otter pup, cradles him into her arms, and puts the bottle to his mouth. He’s a little young yet, but once he sheds his natal coat and hits a few baby-otter milestones (directional swims, back-to-belly movements, can feed himself crab and shrimp), he’ll be matched with a more suitable mom: one of the aquarium’s resident otters.

Recent events have put a spotlight on the aquarium’s otter programs, given the new chapter in the saga of the sassy, surfboard-stealing—and aquarium-born—Otter 841, which Bay Nature reported on in November 2022. Otter 841 was, at last report, on the lam from authorities who planned to remove her permanently from the wild to prevent further human-otter conflicts. (An otter bite is no joke.) The case exemplifies the type of habituation to humans that aquarium staff strive so carefully to avoid.

For now, Otter 841 appears to be a special case (and might well have learned not to fear humans after being released). For two decades the Monterey aquarium has been successfully raising abandoned wild-born otter pups by matching them with surrogate moms, and releasing them back into the wild along the central California coast. The program exists because otters need help—and because they’re a keystone species that play a vital role in keeping our nearshore ecosystems healthy. Once numerous along California’s shores, sea otters were nearly wiped out by fur hunters in the 18th and 19th centuries. Without sea otters around to maintain estuary eelgrass beds and prey on kelp-feeding sea urchins, urchin populations have gone wild. They have devastated kelp forests, which—like trees on land—provide a host of ecosystem services, like sequestering carbon dioxide and providing food or shelter to hundreds of fish species and marine mammals.

The estimated 3,000 southern sea otters that today gambol the central California coast descend entirely from a few dozen animals that in 1938 were discovered near the mouth of Bixby Creek along the Big Sur coast. While the population began to rebound after gaining federal protection in the 1970s, Monterey Bay Aquarium’s sea otter surrogacy has contributed to that population growth since it began in 2001. At Elkhorn Slough, one of three release sites, 37 surrogate-reared pups were released between 2002 and 2016; by 2019, more than half of the sea otters were surrogate-reared otters or their offspring.

Officials mull sea otter reintroduction

Last year, the US Fish and Wildlife Service began exploring the idea of reintroducing sea otters in their historic range, from north of the Golden Gate Bridge to Oregon. If successful, this effort would begin to bridge the gap between California’s southern sea otters and the northern sea otters that occupy the nearshore waters of Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington State. The agency has been holding public meetings to suss out interest. Among those concerned are abalone and commercial sea urchin divers, who worry otters would compete with them for their livelihoods.

If otters are reintroduced, the Monterey Bay surrogacy program could play a key role, given its successes, says Gena Bentall, senior scientist and director at Sea Otter Savvy, a central California program that strives to reduce human-otter conflicts. “Why not take those animals and utilize them as seed populations for reintroduction?” Bentall says. “I think that’s the future of this kind of conservation action.”

Twenty years of surrogacy

Recently, scientists from the Monterey’s sea otter surrogacy program documented the surrogacy program and its outcomes in the journal Biological Conservation. Over the two decades, 10 females served as surrogate moms—some stranded or recaptured as adults, others that had been orphaned pups themselves. In the first meeting, a prospective pair are left alone in an outdoor pool while staff watch on hi-definition video, waiting to see if the adult will share food. Nearly half of pups have bonded with their new moms at the first meeting, and 89 percent within a week.

Once released, surrogate-reared pups survived across a range of habitats, from the estuary to the coastline. Three-quarters of the 64 surrogate-reared otter orphans successfully reacclimated to life in the wild, they found—a survival rate that is comparable to the wild-born population. “Reestablishing the natural mother-pup bond is likely the key to long-term survival,” the researchers wrote. “This crucial relationship reinforces a pup’s social identity and establishes a strong foundation for learning life skills from wild sea otters after release, even without significant prior exposure to the ocean environment.”

How it got started

When the aquarium started rehabbing otters in 1984, staff hand-reared pups around the clock. But that all changed in 2001, when Tula, a resident aquarium otter, gave birth to a stillborn pup just as a wild-born, abandoned pup arrived.

“We had seen it before that a wild mom would adopt a wild pup,” says Sandrine Hazan, the aquarium’s sea otter stranding and rehabilitation manager, who has been with the aquarium since 2008. “That pup was on formula and they just thought, why not put them together? Because the female Tula was lactating. That literally became the birth of the surrogacy program.”

This serendipitous discovery proved invaluable. Surrogate-reared pups did way better than the hand-reared ones, Hazan says. “Those pups had a higher survival rate, they hit developmental milestones sooner, and they were far more likely to assimilate back into the wild.”

What pups learn

On any given day, aquarium surrogates Ivy, Selka, and Kit can be seen swimming lazily around their tank in the public viewing area. During times of rearing, these mothers move to the rehabilitation center where they teach immature and inexperienced pups how to forage and groom themselves, and socialize them to the ways of otter society. Most importantly, the surrogates teach young pups to avoid humans and predators. As an animal that spends its life on or near shore, southern sea otters are susceptible to close interactions and conflicts with humans, who also spend plenty of time at the shore—as the case of Otter 841 has underscored.

Bentall at Sea Otter Savvy says that 841’s early history at the aquarium, and the amount of exposure she’s clearly had to humans, are likely contributing factors.

“As much as [aquarium staffers] try to hide who they are, animals are pretty smart. They can smell things and intuit things that we have no idea of understanding.” Says Bentall.

But Bentall also acknowledges that there are many factors that increase the likelihood of a surfboard-stealing-type conflict—including whether humans have fed her, and her own physiology or personality. Pinpointing why some otters approach humans and why others don’t is a challenge—it runs into a problem Bentall calls the “Swiss cheese effect.”

“All the holes in the Swiss cheese have to line up to get from point A when this otter is born, to point Z where we are today with her needing to be removed from the population,” Bentall says. “We can identify some of those Swiss cheese slices, but we can’t know the entire trajectory.”

“But does it overwhelm the benefits of this program?” Bentall says. “I don’t think so.”

That’s a lotta otters

At the heart of Monterey Bay lies Elkhorn Slough, California’s second-largest estuary, where sea otters go for shelter and to eat small marine species like clams, crabs, and oysters. There, Joe Mancino, owner and longtime manager of Elkhorn Slough Safari, has company journal entries tracking sea otter sightings dating back to 1994, when the Safari began running daily pontoon boat tours. In the early years, sea otter sightings were relatively uncommon, with one to three otters per tour. That began to change in 2002, when the aquarium started releasing surrogate-reared otters into the slough. From 2002 through 2006, sightings steadily rose from only a few per trip to peak around 80 per tour, according to Mancino’s records. Today, the aquarium has stopped releasing otters into Elkhorn Slough but continues to release them into Monterey Bay and Morro Bay. “For an ecosystem to become overpopulated with a threatened species is quite remarkable, and a testament to how effective conservationists’ efforts have been.” Mancino says.