I hadn’t realized how long I had waited to take this walk. I call it a walk and not a trek, a hike, or a backpack because the East Bay Regional Park District’s 28-mile Ohlone Regional Wilderness Trail is such pure delight that to describe it we can leave behind words that imply strenuous work. That is not to say that the walk is not long, or at least it can seem long at the end of a 12-hour, 12-mile day, but its length is one of the reasons I could not wait to get back to it. I like a good long walk, and I had made this one before when I was younger, and now, steeping myself in its wild vitality again, I remain sure that it ranks among our best Bay Area treasures.

I made the hike over three days in March, just a week after the region got the best soaking of the season. Because of the recent rain, the hills were revealing their vernal portfolio of biodiversity and natural history in an almost prideful display, and I followed its trail of living color, a parade of wildflowers, through the sweet, perfumed wind full of the clean, city-free scents of spring in this remote section of the Diablo Range. The Ohlone Regional Wilderness Trail traces a meandering line across one of the largest and most secluded swaths of publicly owned oak woodland left in the East Bay. Undulating from 400 to 3,800 feet over its many miles, from the western terminus below Mission Peak across the range to Livermore’s Del Valle Regional Park and the edge of its reservoir, the trail connects the parklands of Mission Peak Regional Preserve, Sunol Regional Wilderness, Ohlone Regional Wilderness, and Del Valle Regional Park.

Although I walked the trail’s length in spring—arguably the most agreeable time of year to the human interloper—there are always trade-offs. In the summer, the berries present their plump selves in the riparian areas, but that is also the time of flies and stifling heat. In the autumn, the days begin to shorten across the golden fields, but before the rains there is hardly a drop of water anywhere. In the short winter, when the rains come between November and March, green life begins to emerge again, but the ridgeline campsites can be very cold and muddy. It is late March through early May, the season of flowers, that is my favorite time, although this too presents challenges. For one, it is also the season of full-leaf poison oak and its constant encroachment on the trail, creating tunnels of the stuff between the Sunol Visitor Center and the Sunol Backpack Camp.

Day 1

The first morning I start early to cover the roughly four miles that take you up and over Mission Peak, the most crowded stretch of the trail. After descending into the verdant Sunol Valley, I delight in my solitude. Just a few miles from the Interstate 680 corridor to the north and the suburban world of Fremont to the west, I encounter only a couple of other solo hikers, who are happy to give a friendly hello before we move past one another back into our respective lone meditations.

Crossing the stretch of land owned by the San Francisco Water District, I skip over a few dozen streams and pass through meadows dotted with the bold pinks and white of shooting stars. Then I enter the closed canopy of bigleaf maple and buckeye forest before the trail levels out to fields of owl’s clover and Calaveras Road. There is music written across this landscape. It’s an easy place for daydreams, where a kind of synesthesia can take hold. I let my eyes blur and imagine the poppy field as a tapestry of stars—endless constellations that exchange the celestial dome for the green hill. I pretend that the male Sara orangetip butterfly (recognizable because the male’s wing tips lack the white of the female’s) that I saw in the morning at Mission Peak, then again at the Sunol Visitor Center, and then a third time at the Backpack Camp this evening is not just the same species, but the same creature, following me all day. As the heavy, rust-colored sun begins to set in camp, I am treated to a show at golden hour: Two California tortoiseshell butterflies dive-bomb each other in a frenetic dance under the budding blue oaks.

Day 2

Headed into the brightly rising sun on day two, I follow the merry and complex songs of the meadowlarks 15 over a trail of serpentinite and sandstone crisscrossed by splashing creeks and around ponds full of chorus frogs. There is a cinematic quality to the pastureland country of rock and oak. The landscape, draped in the contrasting blanket of purple lupines and bright orange California poppies, unfolds in its unique narrative.

Consider the dominant tree on the trail: our beloved true oak. In my time on the trail, I am able to identify six of the 13 native tree-forming species we have in California: valley oak (Quercus lobata), the biggest oaks in the Ohlone; black oak (Q. kelloggii), which grow near Rose Peak; blue oak (Q. douglasii), the most common oak on the trail; coast live oak (Q. agrifolia), “live” referring to its non-deciduous nature; interior live oak (Q. wislizeni), near Schlieper Rock; and canyon live oak (Q. chrysolepis), our state’s most widely distributed oak species. Every oak tree takes on its form, and when I was young growing up near Mount Diablo, I thought every single tree was its own species. Some of my first memories of nature were of drawing and giving names to individual trees that still stand today—names like “Two Butterflies” or “Mossy Face.” With black fingers spiraling out in an expressive, upward dance, growing as quickly as its deeply furrowed bark will allow, oaks seem to invest decades of artistic, arboreal intention into their own forms and only loosely hold to the morphological guidelines of their respective species.

Most of the oak woodland in the Ohlone Wilderness west of Rose Peak is dominated by valley oak or blue oak. These long-lived trees are among the ecosystem’s keystone organisms, and oak woodlands in general are associated with high biodiversity. Studies in various parts of the state have found approximately 300 vertebrate species, 1,000 plant species, 370 fungus species, and 5,000 invertebrate species associated with oak woodlands.

The trees themselves are living systems that could not survive without assistance from some unlikely sources: fungi and fire. Certain fungi live in symbiotic relationships, called mycorrhizae, with trees’ roots, and deliver nutrients and moisture to the trees while protecting them from some diseases. Low-intensity fires may reduce tree pathologies and invasive species’ competition with oak seedlings. The benefit or risk of fire to an oak is influenced by many factors, including the oak’s species, size, and age, as well as the season, the fuel load, and the fire frequency in its habitat. Most of the Ohlone area has not burned for decades.

In addition to no fire rejuvenation, another impediment to regeneration for young blue oak forests comes from the deer and cattle that roam these hills. While cattle grazing on annual grasses in winter and spring does benefit oak seedlings by reducing plant competition for scarce resources, summer browsing by deer and cattle can impact young oak growth. It is a complex scenario that presents a clear management challenge in terms of assuring sustainability of these woodlands for the future.

In the late afternoon, I find my way to Stewart’s Camp as the sun makes its dusty-rose and striated-indigo exit. The green-to-gray forest comes alive with new sounds held only for the night. Bats click, pop, and squeak as they scour the blue negative space between tree silhouettes for their insect feast. Turkeys chime in with their jovial clucking, and coyotes whistle and moan over the far ridge just before all is revealed as it truly is: the kingdom of the chorus frog! In the 21st century, it is indeed a rare delight to be inundated by this soundscape, the deafening raucousness of these diminutive amphibians, their choral praise to the starlight.

Day 3

Making my way down to Murietta Falls the morning of my third day and knowing that I’ll be enjoying a beer this afternoon back in town, I’m wistful before a scene that is as close to a terrestrial paradise as I will ever know. The long, silver vein of water seems to me so small, so precious and even precarious, vulnerable in its hold here in the Bay Area. Lacing up my boots for the final stretch of the trail, I ponder how geologic time and human time meet for a moment as another plane passes overhead. The water course traces down the cracked rock, as it has been doing for thousands of years, and only by the grace of wise humans will it continue to do so. If my home were a trail, this would be the one. And as I get older, each time I return I become more grateful, and I feel a deeper love for all its parts. Even the lonely roar of the airplanes and the vacant stares of the cows hold bits of magic.

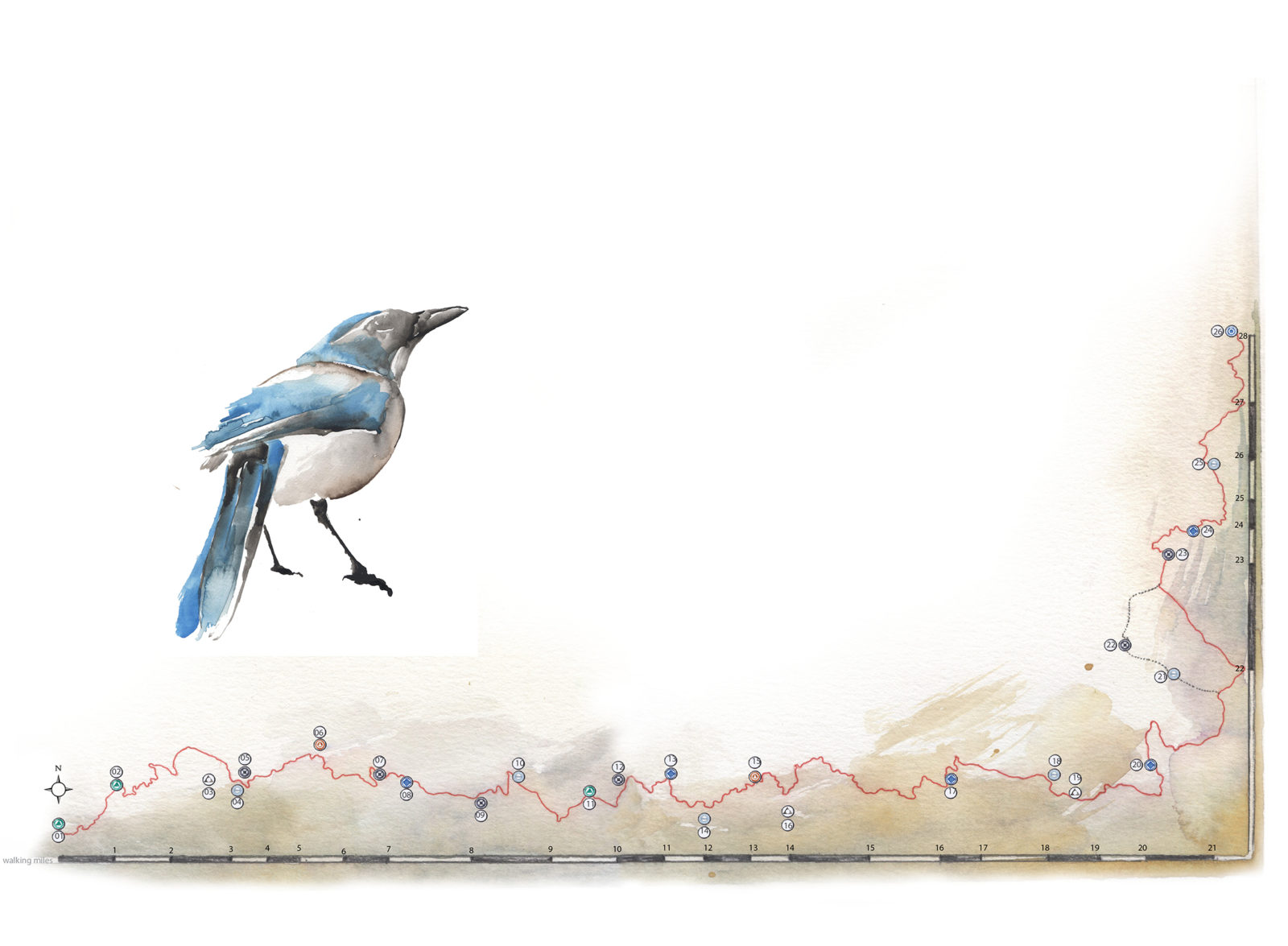

The last section of trail down to Del Valle Regional Park and the reservoir is the steepest, and because of this stretch, I would have to label the trail as moderately difficult, if not strenuous. On the easternmost portion, gray pine trees form thick stands on the north-facing slopes. This gray pine and blue oak forest, interspersed with red-barked madrone and streamside box elder near the north fork of Indian Creek, is habitat for the California scrub jays and Steller’s jays that loudly squawk in the trees and the shrubby toyon, scrub oak, and coffeeberry. The relationship between the trees and the birds is mutually beneficial. Jays bury the tough acorns in scattered locations, caching more than they will eat in any season, and the acorns that survive may sprout. This behavior assists with dispersal and even the passive restoration of oak woodlands. I cross Williams Gulch, thinking the blue oaks here are massive, and I was later happy to learn that one of the most massive examples of the species ever to be documented, nearly 100 feet tall and 48 feet wide, was measured on this trail, deep in this local wilderness.

Even in such places that gingerly hold the title of wilderness, which the Ohlone does, even after centuries of old tensions, along with the adulterations of pastures by planes and pollution, a character holds and is recognizable: Water is the one constant vein in this vernal fecundity. In these hills, as in all of California, water maps a circulatory system for the wilderness body. As I descend from the trail into Del Valle, I picture one last piece of magical transformation, where the trail is not simply a human scratch in the earth across a few hills, but a living circuit, a system of its own making, a vital conduit toward understanding ourselves as much as anything else.