This article has been conserved for you by Sonoma Land Trust.

Last winter’s parade of atmospheric river storms raised water levels in the Bay Area’s creeks, rivers, and reservoirs. Like most water utilities, Santa Clara Valley Water District, which serves the county’s two million people, releases water from its 10 reservoirs ahead of big storms to make space for new runoff. The risk of unplanned flooding was close in January, when creeks were overflowing and Uvas and Almaden Reservoirs were spilling. In response, Valley Water released big flows from its Santa Cruz Mountain reservoirs, and the water rushed down Los Gatos Creek and the Guadalupe River out into San Francisco Bay.

SIDEBAR

The Beavers of Los Gatos

Years before beavers famously returned to Martinez, Los Gatos locals were spotting them in creeks and ponds. How the rodents got there, though—that’s a bit of a rabbit hole.

As Steve Holmes walked along Los Gatos Creek beside Highway 17 in Campbell on a bright February day, not long after the emergency releases, he pointed out mounds of sticks and mud clinging to the banks. The director of South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition, Holmes has spent his decade in retirement clearing trash from streams in service to his love for fish. But another creature’s handiwork has also caught his eye over the years. We’re looking at the remnants of beaver dams blown out through a combination of stormwater runoff and Valley Water releasing its bounty. Trash clung to bushes several feet above the water, marking its peak height. “Do you think the beavers are still here?” I asked.

In recent years, beavers and their handiwork have been spotted in several Bay Area counties: Santa Clara, San Mateo, Contra Costa, Napa, Solano, and Sonoma, and according to a good bit of evidence, they have quietly lived in the Santa Cruz Mountains since the 1990s. Meanwhile, California introduced new policies in 2022 that embrace beavers as partners in supporting biodiversity, healing water systems, and reducing fires. This appreciation, spurred by the work of activists and scientists, is a shift from earlier state policies over past decades that by turns allowed beavers to be hunted for fur or killed as nuisance animals, then protected them, relocated them, and enabled them to be hunted again. Today’s beaver-friendlier approach will catch up California with other western states.

Activists Kate Lundquist and Brock Dolman, founders of the Bring Back the Beaver campaign of the Sonoma-based Occidental Arts & Ecology Center (OAEC), have played a significant role in stoking beaver support, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The environmental advocacy and education nonprofit OAEC’s online guidebook Beaver in California: Creating a Culture of Stewardship, most recently published in 2020, lays out the animal’s history. Prior to Europeans’ arrival in North America, the authors note, there may have been anywhere from 60 million to 400 million beavers on the continent. In much of California, they were as numerous as anywhere.

Beavers are great swimmers but awkward on land, so they often build dams to create pools of water and dig canals, allowing them to harvest plants for food and construction across a wider area, safe from land predators. Historically, as much as one-tenth of North America was beaver-created wetlands. These, along with other wetlands, floodplains, meadows, and forests, played a critical role in the healthy water cycle.

Then came the commercial trappers, who hunted beavers for their dense fur, their castoreum (a glandular secretion) used in perfumes and medicine, and their meat. In the late 18th and 19th centuries Russian, European, and American fur traders were sailing the West Coast, trapping animals. By the early 1940s, California beaver numbers were thought to be as low as 1,300. Settlers who crossed the continent in the wake of trappers found newly dry, flat areas that seemed perfect for building and farming, rich with silt from millennia of water inundation.

However, something important had been lost in the West: reliable water. Beaver removal—as well as settlers cutting forests, straightening waterways, draining wetlands, and leveeing off floodplains—fundamentally altered the plumbing of the continent, speeding water off the land. Groundwater levels fell, no longer supplying streams year-round, and North America became a drier, less ecologically diverse place.

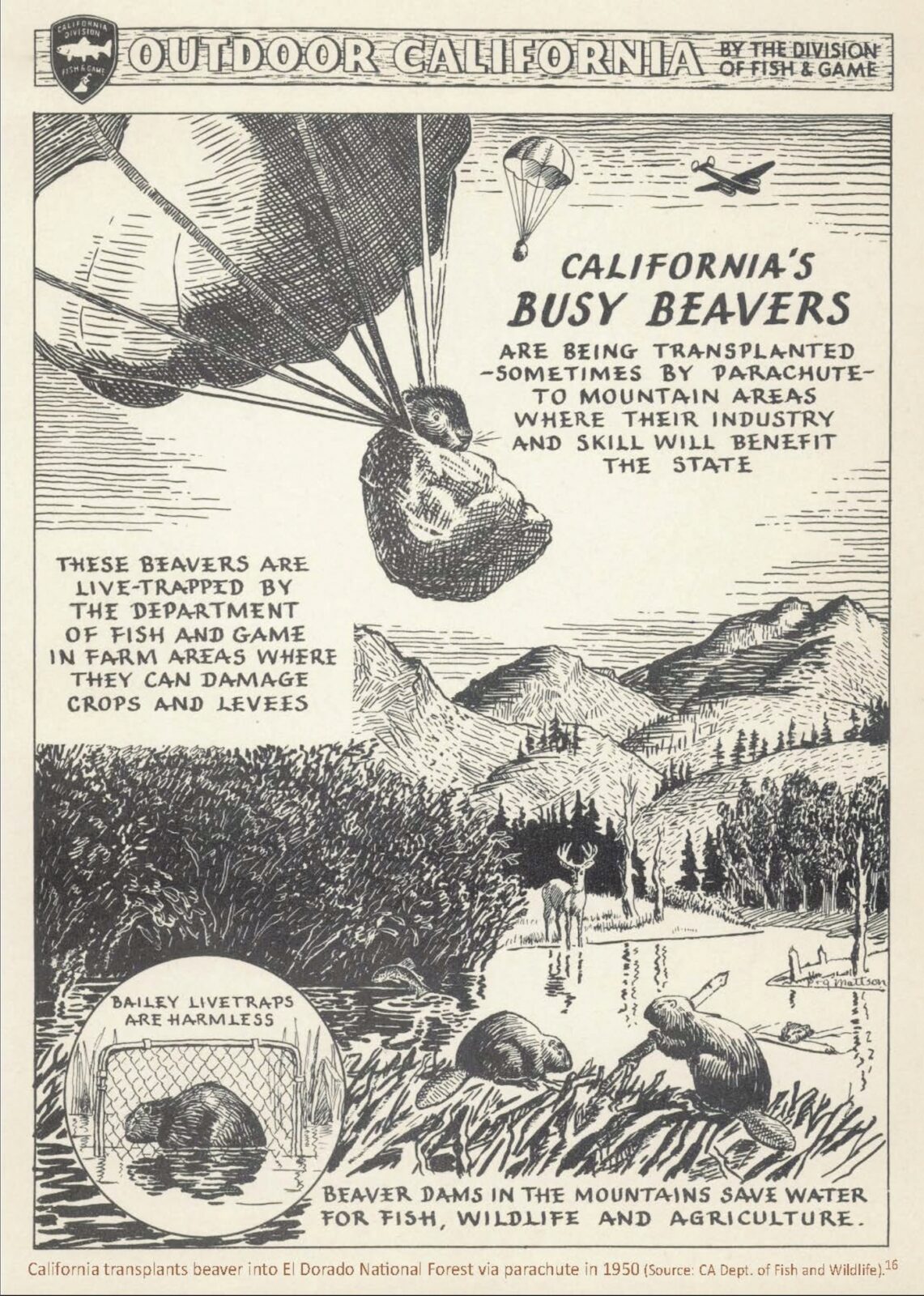

Concerned that beavers might go extinct, the state in 1911 passed a ban on killing them. As beaver populations increased, the state allowed people to trap beavers to protect levees. A few years later, California loosened restrictions around possessing beaver hides. The resulting population crash led the state to protect them again in 1933. Nevertheless, some people appreciated beavers’ skills. Between 1923 and 1950, California relocated 1,221 beavers from towns, cities, and farmlands into more remote watersheds. Division biologist Donald Tappe explained why in a 1942 report: “It is now understood that soil erosion and shortage of water in some places resulted from the destruction of the beavers, which formerly built, and kept in repair, dams on the upper reaches of many streams. The dams were the effective means of impounding waters of the spring runoff, and of distributing them slowly downstream throughout the Summer.”

Idaho’s Department of Fish and Game had come to the same conclusion. Managers there, puzzling over how to move beavers into roadless areas, came up with a solution inspired by World War II airborne divisions: parachuting. In fall 1948, staff dropped 76 beavers in the Idaho mountains. Inspired, California wildlife staff also deployed beavers via parachute, into remote areas of El Dorado National Forest, between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe.

In recent years, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) has not allowed beaver relocations, due to concerns about disease or competition, among other factors, says Erin Chappell, Bay Delta regional manager for CDFW. Instead, the CDFW has often issued depredation permits that provide permission to kill a beaver when people request them, for fear that the animals will cause flooding damage. Wildlife Services, a U.S. federal agency, reported lethally removing 541 beavers in California in 2022, using guns, neck snares, body-grip traps, and other methods. And more beavers are depredated by county departments.

Activists have been pressing California to embrace coexistence instead. In addition to Lundquist and Dolman, others, including the California Indian Environmental Alliance, advocated for the funding of a new beaver restoration program. In 2006, when beavers moved into Alhambra Creek in Martinez and city managers wanted to remove them, Heidi Perryman founded the nonprofit Worth a Dam. Her work organizing a local annual beaver festival and the 2021 California Beaver Summit also brought Bay Area beavers to the public’s attention in the modern era.

In 2019 the national Center for Biological Diversity sued Wildlife Services, alleging that its beaver-killing also harmed endangered species. The result was a pause in depredation. Beavers are now considered ecosystem engineers because their activities create habitat for many other species.

The threat to endangered species is real, Dolman says. In 2021, the minutes from community meetings in California’s Trinity River watershed area showed that a CDFW warden removed a beaver dam on private property against the landowner’s wishes, draining ponds. “The landowner and his family spent hours picking up all the dead coho, steelhead, giant salamanders,” Dolman recounts, “and took … these horrific gothic photos of hundreds of dead animals.” When asked about it, CDFW staff said the incident is under investigation and they offered no additional information.

Activists are working to tackle a long-held belief that beavers weren’t native to much of California. Dolman, Lundquist, Perryman, Rick Lanman, a semiretired doctor who has published journal articles about California wildlife, and others have amassed historical evidence on the presence of beavers in coastal California watersheds and in the Sierra Nevada. Three papers in CDFW’s quarterly journal California Fish and Game and a report for The Nature Conservancy, all published roughly a decade ago, cite extensive trapping records, beaver place names around the state, at least 20 Indigenous groups in California with words for beaver, and evidence of various groups’ use of beavers, as well as a beaver skull at the Smithsonian collected from Saratoga Creek in 1855; teeth and three bones found in the Emeryville Shellmound dating back approximately 700 to 2,600 radiocarbon years; and explorer accounts of beavers alive and dead.

The activists are inspired by science that shows beaver wetlands buffer flood and drought, create firebreaks, and build habitat for other wildlife. In beaver ponds, water slows, dropping sediment and raising eroded beds so streams can reach their floodplains again. Floodplains grow fish food and infiltrate water underground, cleaning it and supplying streams in summer.

In California and elsewhere, beavers’ water storage skills will only increase in value with climate change, say scientists, as more precipitation falls as rain rather than snow. Climate scientists estimate that the Sierra snowpack, which stores about one-third of Californians’ water, could decline nearly 80 percent by 2100 under a high emissions scenario.

Beavers can help bridge that storage deficit, according to research by Benjamin Dittbrenner, founder of Beavers Northwest, which facilitates détente between people and beavers. Tracking 71 beavers he relocated, Dittbrenner found that in rain-dominated basins, beaver ponds increased summer water availability by up to 20 percent.

Wetlands, including those created by beavers, are vital habitat for nearly half of threatened species in the United States. Humans have destroyed more than 90 percent of California’s wetlands.

Along the Los Gatos Creek in Campbell, a family of at least four beavers has carved out a life since at least 2017, according to photographer Julie Kitzenberger. (Julie Kitzenberger)

Beaver water complexes can also act as fire refugia as well as firebreaks, according to ecohydrologist Emily Fairfax of the University of Minnesota, formerly of CSU Channel Islands. The benefits extend beyond the pond because plants can access the higher water table beavers create, making the plants less likely to burn. Evaporation from the ponds and plants’ exhalation of water, called transpiration, also feeds rain. Where beavers have been allowed to expand up and down a waterway, such as in the Methow Valley in Washington, they can create significant firebreaks, Fairfax has found.

Washington state began re-embracing beavers in the late 1990s and early 2000s, motivated by their ability to support declining salmon health as various lethal beaver management strategies were outlawed. Oregon, Wyoming, Utah, and most other western states have followed suit. Last year California finally jumped on the beaver bandwagon, funding five permanent staff positions dedicated to beaver management in the CDFW. Chad Dibble, the department’s deputy director of wildlife and fisheries, says some land managers tell him they want beavers for the creatures’ ability to increase water supply, restore ecosystems, and ramp up resilience to climate change and wildfire.

On a public call hosted by the department in May 2023, beaver program manager Valerie Cook outlined four goals: developing a management and restoration plan; promoting human-beaver coexistence, which involves updating the depredation policy for when it’s permissible to kill beavers; relocating beavers, sourced from department lands or from depredation requests, for the purpose of ecosystem restoration; and conducting public outreach and education.

Fairfax calls California’s new support of beaver restoration “huge and amazing.” The governor’s authorization “very explicitly says that we want to bring back beavers to California to help us deal with the threats of climate change because there’s so much value in what they provide on the landscape.”

Development such as paved areas, buildings, and farms in floodplains and wetlands increases flooding, and as a result much of our water infrastructure is designed to rush water off the land, enclosing it in narrow pipes and straightened concrete channels. That approach is at cross purposes with beavers’ goal of slowing water to make ponds so they can swim around safely. Human fears that beavers will cause flooding of infrastructure drives landowners to pull apart beaver dams, blow them up, or request depredation permits.

In June, CDFW’s beaver team published new guidelines for depredation. Landowners must first take all possible nonlethal measures to prevent damage to infrastructure and crops. And if their land spans the range of threatened or endangered species that depend on beaver wetlands, the department will add protections for them. This policy is in line with a 2019 petition OAEC filed with California Fish and Game Commission, says Dolman.

The department can still issue depredation permits if it sees an imminent threat to public safety. “Depredation permits are a tough one,” Dibble says. But “where there’s public safety concerns with our existing infrastructure,” he acknowledges, management sometimes includes killing beavers.

Yet removal is only a temporary fix in most cases. In Washington state, Molly Alves, wildlife biologist and manager of the Tulalip Beaver Project, relocates beavers that have conflicts with humans. “Removing beavers just opens up prime beaver habitat for the next family that comes across it,” Alves says. “Trapping is a short-term solution to a long-term problem. If you have beavers now, you’re going to have beavers again.”

Beaver believers have developed tools to help people and beavers agree on water management. The pond leveler is a pipe that passes through dams, lowering the water level. The key is to keep the outlet underwater, to avoid the sound of running water that prompts beavers to fix the leak. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has developed its own version in collaboration with OAEC called the “Beaver Back Saver,” says Valerie Cook.

Another coexistence strategy is to expect beavers to move in and design infrastructure that will accommodate their activities. Dibble says the state will educate land managers about redesigning culverts and roads to avoid future conflicts. “We’re changing our tune,” he says, citing wildlife overpasses and wide culverts that allow multiple species to pass easily.

In parks, where streams often remain on the surface, such strategies include leaving space around the edges of water and building elevated walkways for people. Managers might also replant willows and other beaver food sources as the animals harvest them and protect humans’ favorite trees with wire mesh or sanded paint around the trunk to prevent their felling.

To identify priority areas for restoration, historical ecologists study where streams, rivers, and wetlands traveled before European settlers altered them. San Francisco Estuary Institute has done this work for Coyote Creek, western Santa Clara Valley, the Peninsula, Sonoma Valley, and others. One recommendation, reconnecting Calabazas and San Tomas Aquino Creeks with marshes near Alviso, was funded last summer by the EPA.

When coexistence remains elusive, California will now support relocations as an alternative to euthanasia, although Dibble notes that not all beavers in conflict will be relocated. Dibble says CDFW hopes to do its first modern beaver relocations by year’s end—no more parachutes. The department is taking advice from a technical advisory group, including Alves. In 2019 I got a sense of what relocations entail—and met a few beavers—when I shadowed her in Washington state.

That sunny September day, she and then assistant wildlife biologist David Bailey collected a beaver from a live trap they’d set in a pond at the end of a suburban street in Seattle. The beaver sat on his tush, flat tail out in front of him, webbed back feet with long claws resting on top, lush fur sticking out through the cage. He held his little forepaws together in front of his chest, as if in prayer. His nose appeared larger than his front hands, and the eye that I could see was quite small, dark brown, and squinted half closed.

Alves and Bailey loaded the beaver into the back of their Suburban, where he sat quietly in a cage covered by a sheet to reduce stimulation. We drove to the Tulalip Tribes’ fish hatchery, which would be the beaver’s temporary home. The long concrete tanks, called raceways, had dry platforms for sleeping, and the water was festooned with boughs and branches for snacks. Because beavers are family animals, the team holds them here until it can capture the whole clan for relocation. Releasing them in family groups helps relocation success rates.

The team would determine the fate for today’s fellow after an examination. Although we had been using male pronouns, it’s impossible to tell a beaver’s sex just by looking. To find out, Alves and Bailey wrapped him tightly in canvas. Bailey applied pressure to push out the beaver’s anal gland from the cloaca, an orifice for both reproduction and waste. He squeezed it to release oil from the castor sac. Old cheese smell signifies a female beaver, motor oil a male.

“Ah, the glamour of my job,” laughed Alves, leaning in to absorb a bit of the oil with a paper towel. We each gave it a cautious sniff: not awful, but getting there. The pungent odor did resemble motor oil. This was likely the dad of the clan they’d caught at the same lake earlier that week. He would be reunited with his family at the hatchery for a few days until Alves could line up a relocation spot.

Three beavers from another family were ready for relocation, so Alves, Bailey, and interns loaded their cages into a truck for a drive into Mount Baker Snoqualmie National Forest. When we arrived, they carried the beavers to the stream. Alves opened the first cage in front of a standing cone of logs the humans had assembled in the water to give the beavers refuge from predators. The beaver hesitated, then walked slowly into the dark opening ahead, flat tail dragging behind. Then she disappeared into the water. In a flash, someone moved the empty cage and lined up the second beaver, who followed suit. Then it was the third beaver’s turn.

Researchers estimate that beavers are at only about 10 percent of historical numbers. “They’ve shown they are resilient,” says Dolman, “but there’s a lot more we could be doing to support them.” He suggests following beavers’ lead to increase water quality and quantity by restoring wetlands, floodplains, forests, and meadows and reducing pollution in urban runoff by infiltrating water underground throughout cities.

In the South Bay, Valley Water has so far taken a live-and-let-live approach to beavers, says Jae Abel, a biologist with the utility: “If they don’t get in the way, we won’t be paying attention too much.”

Unhoused people have also taken up residence along the banks of some waterways, including the Guadalupe River and Los Gatos Creek. With South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition director Steve Holmes, I walked down into the floodplain of the Guadalupe River near downtown San José. Trash was everywhere. Holmes sighed. “We’ve removed nearly 1.25 million pounds of trash,” he said, adding that he cleans the same areas again and again. “The whole thing is just really frustrating.” But his commitment to the animals keeps him going.

By June he had more encouraging news. San José mayor Matt Mahan was investing in short-term housing for people living in creek corridors. In April the federal Housing and Urban Development agency gave Santa Clara County $11 million to tackle homelessness, which joins Measure A, the nearly $1 billion bond measure that Santa Clara County voters approved in 2016 for affordable housing. And in June the EPA provided $3 million to clean up nine Santa Clara County waterways.

Despite the challenges, Holmes is inspired by beavers’ tenacity. “We have these salmon and beaver that have moved in and are making a pretty healthy living for the conditions that they’re facing,” he said. In response to my question on Los Gatos Creek about whether the beavers are still there, he pointed to trees with gnaws so fresh that bright wood chips still littered the rock below. “Absolutely.”

Correction: The print version of this piece says that Julie Kitzenberger’s photos were taken at San Tomas Aquino Creek in Campbell, but they were taken at Los Gatos Creek in Campbell. This has been corrected here.

Correction: The print version of this piece says that OAEC filed a commission with California Department of Fish and Wildlife, but this petition was filed with CA Fish and Game Commission. This has been corrected here.