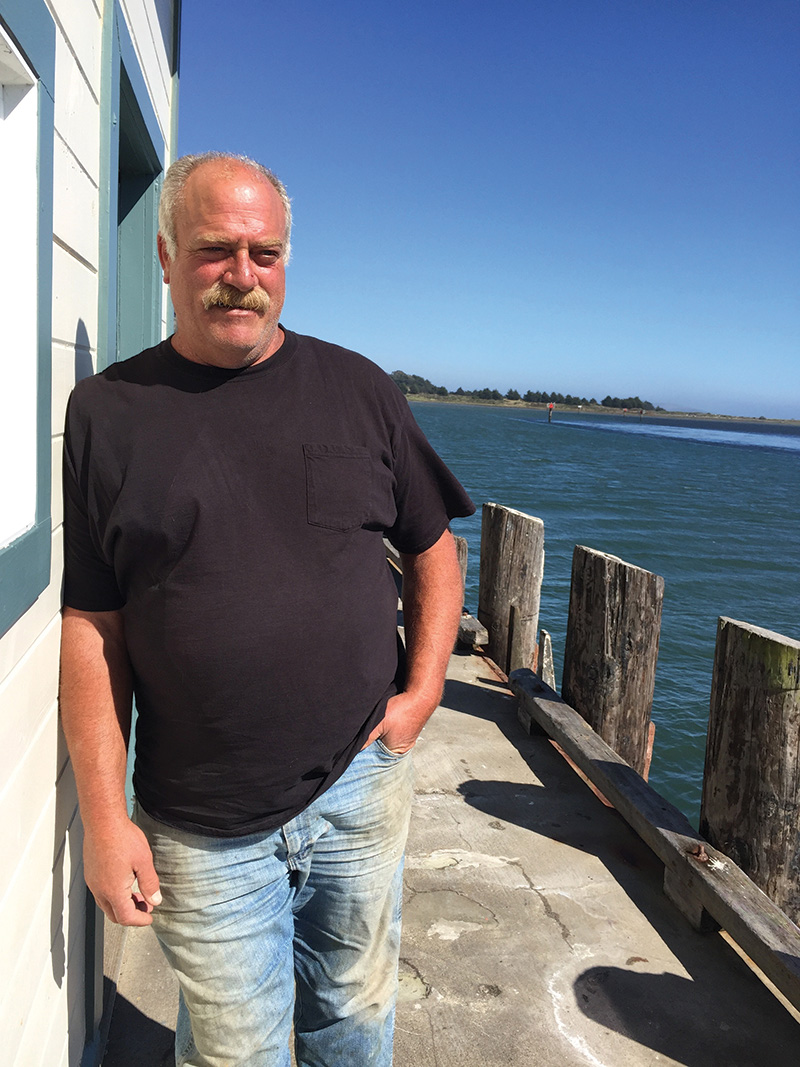

On a windy summer afternoon in Bodega Bay, Mark Gentry pauses for an afternoon yerba mate on the dock by his boat, whose deck is littered with crusty lines and vinyl yellow “bib” coveralls. Tall piles of circular mesh crab pots sit idle nearby; this year’s crab season ended early as whales moved through the area. I’m visiting Gentry to ask him about the new California crabbing regulations intended to protect those whales. As a marine biologist, I understand the issue from an environmental angle. Now I want to hear the crabbers’ perspective.

Gentry has been fishing in Bodega since before he could drive, he tells me as the blast of a distant foghorn vibrates through the air. In his 40-year career, he has seen a lot of change. In the first half of the 20th century, the population of humpback whales in the North Pacific plummeted from 15,000 to 1,200 due to uncontrolled whaling. But after their designation as an endangered species and a subsequent whaling moratorium, populations rebounded significantly.

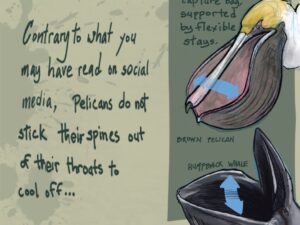

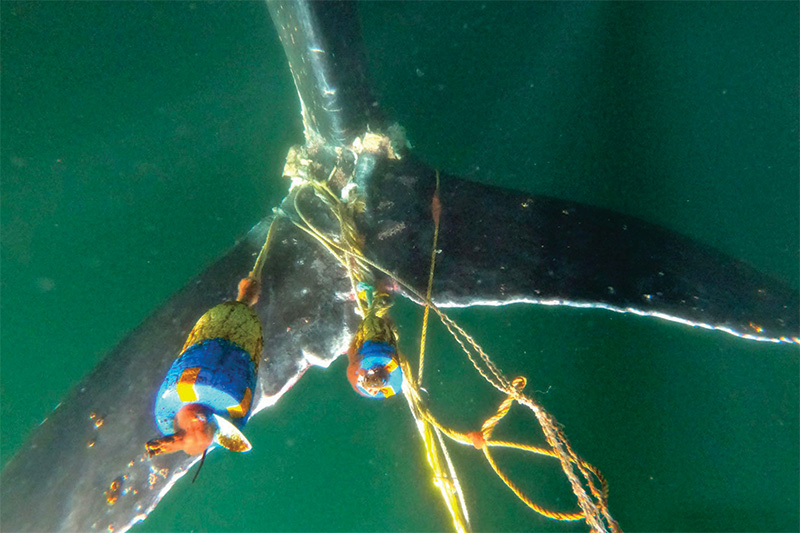

Then, in 2014, a climate-change-related marine heat wave triggered massive ecosystem shifts, and the humpbacks were forced to switch away from krill to a primarily anchovy diet. As whales followed the schooling fish closer to shore, the thousands of crab pots that have long bobbed by the coast from November to July suddenly transformed into a deadly gauntlet, with whales tangling in the vertical lines that attach floating buoys to pots on the seafloor. In response, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit in 2017 against the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, alleging that these whale deaths constituted illegal take of endangered species. Gentry and his fellow fishermen found themselves thrust into the middle of a fraught environmental debate—and, after the lawsuit’s settlement, subject to a bevy of new regulations.

Since 2015, crabber Dick Ogg says he and his colleagues have been doing “everything we can to fish alongside the whales and coexist with them,” including starting a lost gear removal program and working to remove potentially dangerous excess slack from buoy lines. They even voluntarily delayed the 2019-2020 crabbing season due to high whale activity.

CDFW senior scientist Ryan Bartling points out that these programs weren’t just implemented by crabbers but actually suggested by them, as part of a working group of fishermen, regulators, and nonprofit representatives who convened to find solutions. “The fishermen absolutely helped guide the proposed regulations,” he says, calling them “our eyes and ears on the ocean.” The effort seems to be working: of the six humpback entanglements this year, only one definitively involved California commercial crab gear, a significant improvement from 19 entanglements in 2016.

But tension remains in Bodega Bay. Fed up with what they see as too-restrictive regulations in the face of good-faith efforts, another faction of crabbers formed the California Coast Crab Association to advocate for their own interests, including pushing back on gear requirements suggested by environmental groups. “Pop-up gear,” for example, reduces vertical lines that might entangle whales by instead using buoys that sit on the seafloor until an acoustic signal from a nearby boat releases them. But the CCCA argues that the recent progress shows the new technology isn’t necessary—and that buying the significantly more expensive gear would put most crabbers out of business.

Gentry understands that the continuation of the fishery depends on protecting the health of the ecosystem. “I’m a caring person too,” he says. “I don’t want to see these whales go away.” He feels ignored, however, in policy discussions about the best way forward. “It’s incredibly frustrating. Why does that Ph.D. mean more than what I’ve seen for 40 years out there, 22 hours a day?”

On the dock as the fog rolls in, I empathize with Gentry’s frustration and can’t help but hope for a way for all parties to hear each other better. He takes a sip of his yerba mate, broken fingernails hinting at a long life at sea, and predicts the new regulations will force out small-scale fishermen like him. “Those are the guys you want in the industry,” he says with a sigh. “They’re the ones doing things sustainably, and they’re going to be the least able to afford to stay.”