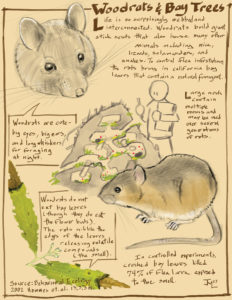

Woodrats, pack rats, and trade rats are all common names for the same remarkable rodent genus, Neotoma. Our local species, the dusky-footed woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes), has a nice multicolor coat—unlike the nasty nonnative Norway and black rats, all too common in urban areas. It’s also extremely cute, with big Mickey Mouse ears and a lovely, lightly fuzzy tail. Yes, I am biased.

If you’re a hiker, it’s hard not to notice their strikingly large nests, which can be three to six feet high, up to eight feet across—approaching the size of a Volkswagen bug or my stack of unread New Yorkers—and often built right on the ground. Like us humans, woodrats have very particular requirements for their homes. They don’t like light (not even moonlight) and so prefer densely shaded areas, especially near water. But they also need to keep their fur dry for good health. Not too dry or too wet. Goldilocks with whiskers!

Woodrats are sometimes called pack rats because they love to collect and store various kinds of junk, much like my former mother-in-law did. And often when they are carrying an item and encounter another prize they consider more enticing, they’ll put down what they’re carrying and abscond with the new treasure—hence the other common name, trade rat. (They are especially attracted to shiny objects…again like my mother-in-law.) Folks living near these critters have reported missing shoes, lace curtains, crackers, soap, wallpaper, and even gum wrappers. Why someone missed gum wrappers is unclear to me.

Woodrat nests are especially easy to find in the winter, after the understory shrubs have dropped their leaves. Nearly every coast live oak forest or willow thicket hosts a few nests. You might find anywhere from 10 to 100 other nests in close proximity, since woodrats thrive in extended colonies of related females. During the winter and spring breeding season, male woodrats move through these nests searching for females in heat. No messing around for these rats; they are monogamous, at least for the time it takes to raise a brood.

What might seem like a haphazard assemblage of branches, stems, leaves, bones, shredded bark, grass, and basically whatever material is easily available (including wire, glass, and old shoes) belies a very complicated interior design. First, woodrats are fastidious housekeepers, with separate areas for pooping, which they clean out regularly. Nests tend to have many tunnels, entrances, and exits. Woodrats build specific chambers for sleeping, giving birth, and nursing and often incorporate their tchotchke collections into their homes as decoration of sorts. They maintain several pantries for stored food, including a room for aging poisonous toyon leaves. They are the rare mammals that can eat these leaves, which contain toxic-level cyanide compounds; their leaching rooms help break down those toxins to make the leaves edible.

Some woodrat nests are over 60 years old, passed down through the generations. Because of their size, the nests make great habitat for other animals, especially the California mouse—so a woodrat could complain about having a mouse problem!—plus salamanders, frogs, lizards, and even snakes. The general presumption among naturalists is that woodrat offspring inherit the nests of their parents, adding on to them over time. Housing is even a problem in this part of the Bay Area!

Woodrats might build some of the most remarkable mammal nests in the region, but they’re definitely not unique. A well-constructed home provides protection from predators, shelter from the elements, and thermoregulation, allowing a creature to create an ideal environment that protects it and its offspring from the vagaries of the outside world. Other local mammals, such as western gray squirrels, river otters, and beavers, also create nests, dens, or lodges. Our closest relatives, bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas, also build simple “nests” every night—basically glorified mattresses. And of course, one primate has taken this nest building to the extreme. Just look at the Taj Mahal.

If you’d like to see a woodrat nest for yourself (at least the outside!), check out the Lafayette Reservoir’s Lakeside Trail Loop in the East Bay or the well-named Dusky-Footed Woodrat Trail at Pulgas Ridge Open Space Preserve in the hills above San Carlos.

.jpg)