To stand on top of Mount Umunhum is to step back in time. Up here at 3,486 feet, spring blossoms and buzzes and a cool wind blows, while down below you can almost watch San Jose roasting under the July sun. At these heights winter is harsher and longer, causing spring on the mountain to begin a month or more later than in the Santa Clara Valley below. Colorful blooms lure butterflies and hummingbirds to the summit, where they seem to congregate, a phenomenon so long a part of the mountain’s existence the region’s Ohlone Indians called it “the resting place of the hummingbird,” or umunhum.

For decades, nature’s quirks have carried on here without much of an audience. Soon, that will change. Umunhum’s 12-acre mountaintop, with its rare panoramic views of the Bay Area, will open to all after being off-limits to the general public since the Almaden Air Force Station became operational in 1958. An interpretive center and almost four miles of new trails for hikers, mountain bikers, and horseback riders are under construction. The grand opening, slated for mid-September 2017, comes after years of logistical wrangling by the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District (MROSD) to include the mountaintop in the surrounding 18,000 acres of the Sierra Azul Open Space Preserve.

“It’s time for Mount Umunhum to take its place in the green circle,” says district general manager Steve Abbors, referring to the swath of open spaces that ring the Bay Area.

The Summit

Opening the mountaintop has been a long time—and almost $20 million of MROSD’s Measure AA funding—in coming. MROSD purchased the site from the military in 1986 for $260,000, but planning for the overhaul only began in earnest after 2009, when the district received $3.2 million from the federal government to remove toxic waste from the site.

After that massive cleanup, all that remain of the mountain’s former military life are a flat top—the ridge was leveled for buildings—and a squat five-story tower, known to locals as “the Cube.” This Cold War remnant, which housed a radar installation from 1958 until 1980, appears at odds with the conservation space. Yet supporters rallied hard for its historic building designation, a status granted last summer by unanimous vote of the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors.

Both the mountain and the tower have long been iconic visual references for area residents, notes Bern Smith, trail director for the Bay Area Ridge Trail Council. A seasoned hiker and cyclist, he promises that anyone who’s seen the landmarks from afar will get “a whole different feel from the top.”

He’s right. Mount Umunhum may not be the highest of the Bay Area’s peaks, a commanding crowd that includes Mount Hamilton (elevation 4,200 feet) to the east, Mount Diablo (3,849 feet) farther north, Loma Prieta (3,786 feet) just south, and Mount St. Helena in Napa, which stands at 4,341 feet. (Mount Tamalpais, just north of the Golden Gate Bridge, tops out at 2,575 feet.) But the view doesn’t feel small. On a clear day, the vistas sweep over hundreds of miles, sometimes all the way to the Sierra Nevada. “These elevated points add a tremendous expansion of perspective, and Mount Um is one of those places,” Smith says. “It will be a keystone destination for the Ridge Trail.”

Remember those words when you’re standing on the summit taking in the 360-degree view, a stiff breeze tousling your hair. If you turn your back to the vast blue of the Pacific Ocean and gaze above the urbanized valley floor, you can trace the rugged green ridgeline—punctuated by the white dome of Mount Hamilton’s Lick Observatory—around the Bay. It’s breathtaking; it also feels breath-giving.

“Viewsheds from high elevations are often seen as sacred,” says Mark Hylkema, a tribal liaison and archaeologist for California Department of Parks and Recreation. “Places like this trigger a sense of the holy.”

For the Amah Mutsun, descendants of tribal groups that once populated the San Juan Valley, an area that radiated outward from the Pajaro River basin, Mount Umunhum is the place the story of creation began. “The top of mountain is where our ancestors came to pray, to be closer to the creator,” says Valentin Lopez, the tribal chairman.

MROSD moved forward with the summit restoration, the Amah Mutsun were invited to partner with the district on the project—an alliance that brought members of the tribal band back to this land for the first time in centuries. When the mountaintop reopens, a ceremonial space awaits the Amah Mutsun, a place of contemplation that will be available to all visitors.

Lopez hopes to spread awareness of the tribal band’s ethos about the land, a view that goes back millennia and is steeped in traditional knowledge and nurturing relationships with animals and plants. It includes the tale of Hummingbird, a creature the Amah Mutsun credit with bringing fire to their people. In part of the tribal creation story, Hummingbird and a handful of other birds were hungry and needed fire to cook their food. Hummingbird went to get fire from the Badger People underground, but they refused to share it. When Hummingbird returned a second time, the Badger People hid the fire under a deerskin. But the skin had a hole in it where an arrow had gone through, and clever Hummingbird reached in with his long narrow beak to remove a hot ember. As he carried the ember it flamed, turning his throat a brilliant red. Anna’s hummingbird, easily recognized by its ruby-colored breast, is a year-round resident and frequent flier on Mount Umunhum, enticed by the California fuchsia and red beardtongue.

The Lay of the Land

The story of Mount Umunhum reaches back much further than human occupation. It traces the evolution of some species and the ongoing shifts of the underlying rock foundation. “As you go up in elevation, you go back in time,” says Ken Hickman, a naturalist and wildlife researcher who’s been surveying the mountain’s flora and fauna for MROSD the last few years. Mount Umunhum’s long winter—with rainfall, ice, and snow, and winds that can howl at more than 100 miles per hour—sets the stage for a late spring. But the mountain’s eclectic flora and fauna are drawn to the summit by more than wild weather.

Likely due to Umunhum’s elevation and location on the inner edge of the Santa Cruz Mountains, four different plant communities converge at the summit: chaparral, pine woodland, mixed evergreen forest, and summit “rock gardens.” These plant communities include species typically found across the valley in the Hamilton Range and to the south in the Santa Lucia Range, such as oak violet, whitestem rabbitbrush, and Brewer’s rockcress, which haven’t been found elsewhere in the Santa Cruz Mountains, Hickman says. Other species that make their home here are uncommon relicts like the California nutmeg tree (Torreya californica), “a conifer from the time of the dinosaurs,” Hickman says, “with needles like a redwood, the bark of an elm, and crazy-looking fruits instead of cones.” Only six species in the Torreya genus are left in the world.

There’s also the geology. With a complex of faults beneath the mountain—including the infamous San Andreas Fault along its western flank—the soil is full of serpentinite, a rock that contains too much chromium and nickel and too little nitrogen to allow many plants to thrive. (It’s also our state rock and a source of asbestos ore.) Yet here the Mount Hamilton fountain thistle and Loma Prieta leather root have adapted to grow on seeps where water moistens the surfaces of these nutrient-poor rocks. (Another rock type found around the summit is Franciscan chert, a hard rock brought to the surface by tectonic uplift and used by native peoples to make arrowheads and other sharp-edged tools.)

So far, Hickman and his colleagues have documented 14 mammal species, 60 birds, 8 reptiles, 25 butterflies, and 352 different plant species around the Umunhum summit, and they’re sending “voucher specimens” of the plants to the Carl Sharsmith Herbarium at nearby San Jose State University. It’s the most complete survey of life on the mountaintop to date.

Still, he’s pleased to point out a bouquet of rock buckwheat erupting from an outcropping—a favorite plant of butterflies. “Here’s another one of the crossovers from Mount Hamilton,” he says. “Doesn’t grow anywhere else in the Santa Cruz Mountains. I joke that ‘Lord Hamilton’ sent them over here to woo ‘Lady Um.’”

The Trail

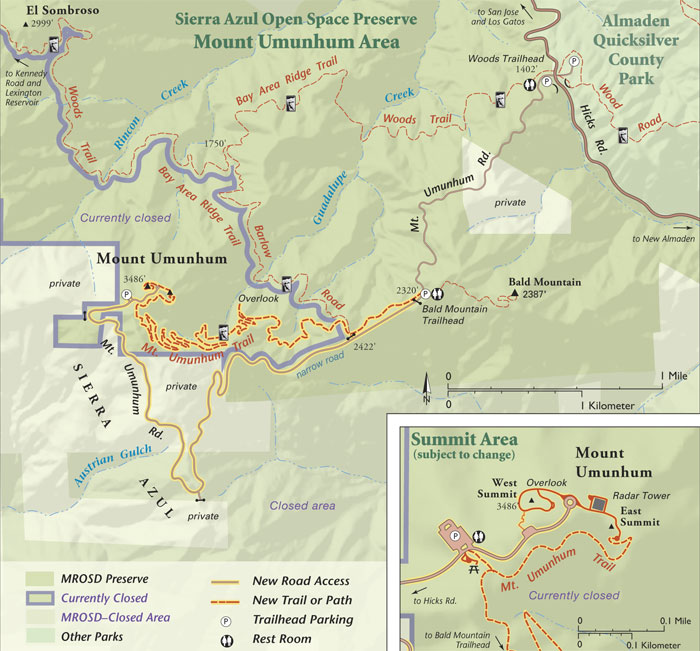

I feel lucky to have Hickman as my guide as we leisurely make our way down the trail-in-progress that will offer visitors a scenic descent from the trailhead shelter near the summit to the Bald Mountain parking lot. Close to four miles long, the trail traverses an elevation change of 1,165 feet. At the 0.4 mile marker, there’s a turn off that ultimately connects with the Bay Area Ridge Trail, which runs through the Sierra Azul Open Space Preserve and beyond.

We start at the summit, where drops of water slowly coalesce under the scree, eventually gathering downslope to become the headwaters for Guadalupe and Rincon creeks. Even on a hot day, it’s a comfortable walk that winds, by turns, under a canopy of madrones—readily recognized by their peeling red-brown bark—and then along less-shaded trail. Sometimes it feels like the Sierra foothills. And then we pass lots of big berry manzanitas, one of the many fruit-bearing shrubs that draw gray foxes and overwintering birds, Hickman notes.

In open areas there are pockets of grassland species, stands of white-flowered yampa with tuber roots that were a staple in the Ohlone Indian diet, and tarweed plants whose seeds (a favorite with many birds) were gathered and ground into flour. The lizards hustle for cover and I look out for snakes—perhaps not for the same reasons that Hickman might.

Remember, they are an exotic species in the Western United States, and are rapidly increasing their geographic range and range of habitats. Are they outcompeting or excluding native species in the process? How would we know? We have done almost nothing to monitor changes in the assemblage of mushroom species in areas before and and after the incursion of death caps.

Further Reading

Pringle et al, “The ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America,” Molecular Biology 2009

Lockhart et al, “Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017

Battalani et al, “Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize in Europe increases due to climate change,” Scientific Reports 2016

Details: It’s worth noting that we started our one-way hike from the summit, enjoying an all-downhill experience. Once the restoration is complete and the trail opens, an upper trailhead shelter will be located less than a half-mile from the top of the mountain, with parking available there, as well as a bathroom and a water trough for horses. But there won’t be any water sources for people, so be sure to bring plenty to drink.

This trailhead is also where cyclists and equestrians must exit the trail; the remaining climb to the summit is steep and not constructed for multiuse access. However, cyclists and riders can still get to the top via the road.

The entire Mount Umunhum area is currently closed to dogs. It’s also forbidden for visitors to leave dogs behind in vehicles, which puts the animal at risk for heatstroke.

Getting to the mountain might not be the easiest part: Although the roads will be open for public use, the twists, turns, and narrow passage make for slow going. But that shouldn’t keep anyone away.

The trail is quiet at midday, with the occasional chorus of cicadas and rustling of birds in the underbrush. I spy a dusky-footed wood rat stick house, a surprisingly stout affair of thick twigs stacked into a foot-high shelter. Twice we’ve spotted scat at the trail’s edge, and we speculate about bobcats and mountain lions. We zig and zag across streams (now with bridges constructed to cross them) and pass a “dwarf forest” of leather oaks that typically grow as large shrubs in chaparral. But here, Hickman notes, fire cleared the ground and when the oaks grew back all at once, their density and competition for the sun, along with the nutrient-poor soils, caused them to grow like a grove of small, upright trees.

Soon we stop to check one of Hickman’s camera traps, set to overlook a small natural water hole less than 20 feet off the trail. He’s been setting up his digital cameras—rigged with motion sensors and a tough outer casing—at spots where wildlife will likely show up. It’s been two weeks since he last checked this one, and I’m eager to see who made an appearance. Hickman’s not surprised by any of the images: black-tailed deer, two gray foxes, a Merriam’s chipmunk, western screech owls, a band-tailed pigeon, a yellow warbler, and a black-throated gray warbler, among others.

Another camera, set on a chaparral slope, has captured views of a bobcat, more gray foxes, a brush rabbit, scrub jays, blue-gray gnatcatchers, a California thrasher, and a spotted towhee. Hickman’s cameras have also caught coyote and mountain lions, but he’s really hoping for a cameo of a ring-tailed cat or a spotted skunk. They’ve been documented in the general area, he says. Even though he’s set traps near water and madrone trees with berries to spare—a ringtail favorite, he says—no luck yet.

“One neat detail,” Hickman notes about this small sample set, is the way animals stick to their habitats. “Even though the [camera trap] locations were quite close together, you won’t catch the California thrasher in the forest, or those warblers in the chaparral. But the scrub jays, they’ll go everywhere.”

When the trail angles off to a vista point overlooking Guadalupe Creek, we can look back up toward the sheer southeastern face of Mount Umunhum. Already it seems far away. Golden eagles have been spotted around here, but they aren’t soaring overhead today. Instead, Hickman draws my attention toward terraced places along the slope, telling me how Bigelow’s spikemoss helps create the terraces by binding loose rocks and soil together with its roots, allowing moisture to collect and seeds to grow in those steep spots. They anchor rock garden plants such as canyon live-forever and the rare Diablo snakeroot.

It’s an easy stretch from there to the Bald Mountain parking lot and a staging area for horse trailers, an amenity Los Gatos horsewoman Magda Bartilsson is looking forward to using. “It’s always good for equestrians to have connectivity between the public lands,” she says. “How lucky we are to have this open space available to us. As soon as it’s open, we’re going!”

The mountaintop will open soon for other reasons too, as MROSD’s Abbors notes. “Open space has always been thought of as a nice thing—but it’s absolutely critical on a planetary scale,” he says. “We’ve done a lot of work on Mt. Umunhum, but in terms of restoration, we’ve still got a lot of time to make up.”