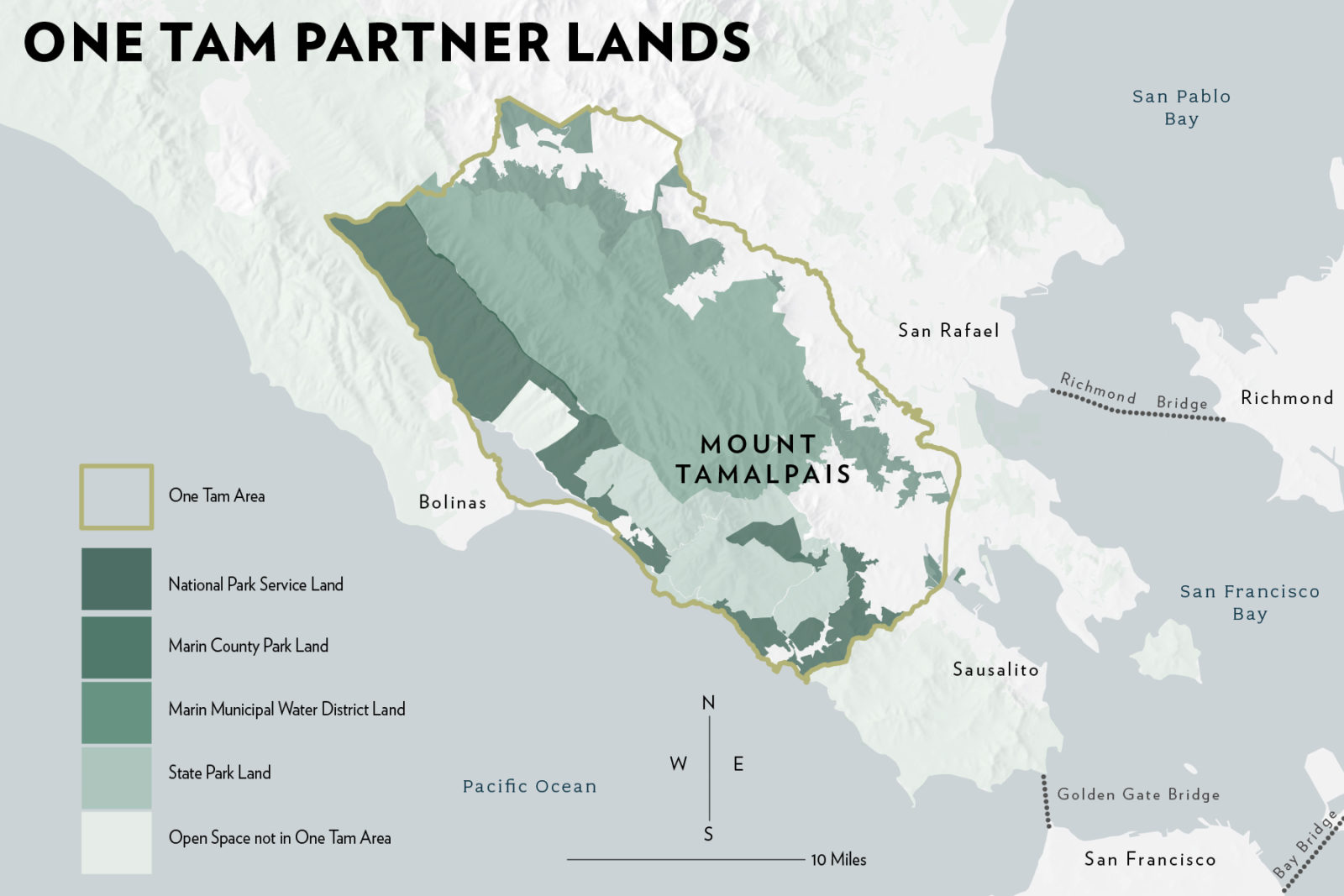

From its peak, Mount Tamalpais in Marin County unfolds into a multitude of microhabitats: fog-sodden redwood forests, oak woodlands, wetlands, grasslands, lakes, and scrub- and chaparral-covered ranges, all the way down to the chilly waters of the Pacific.

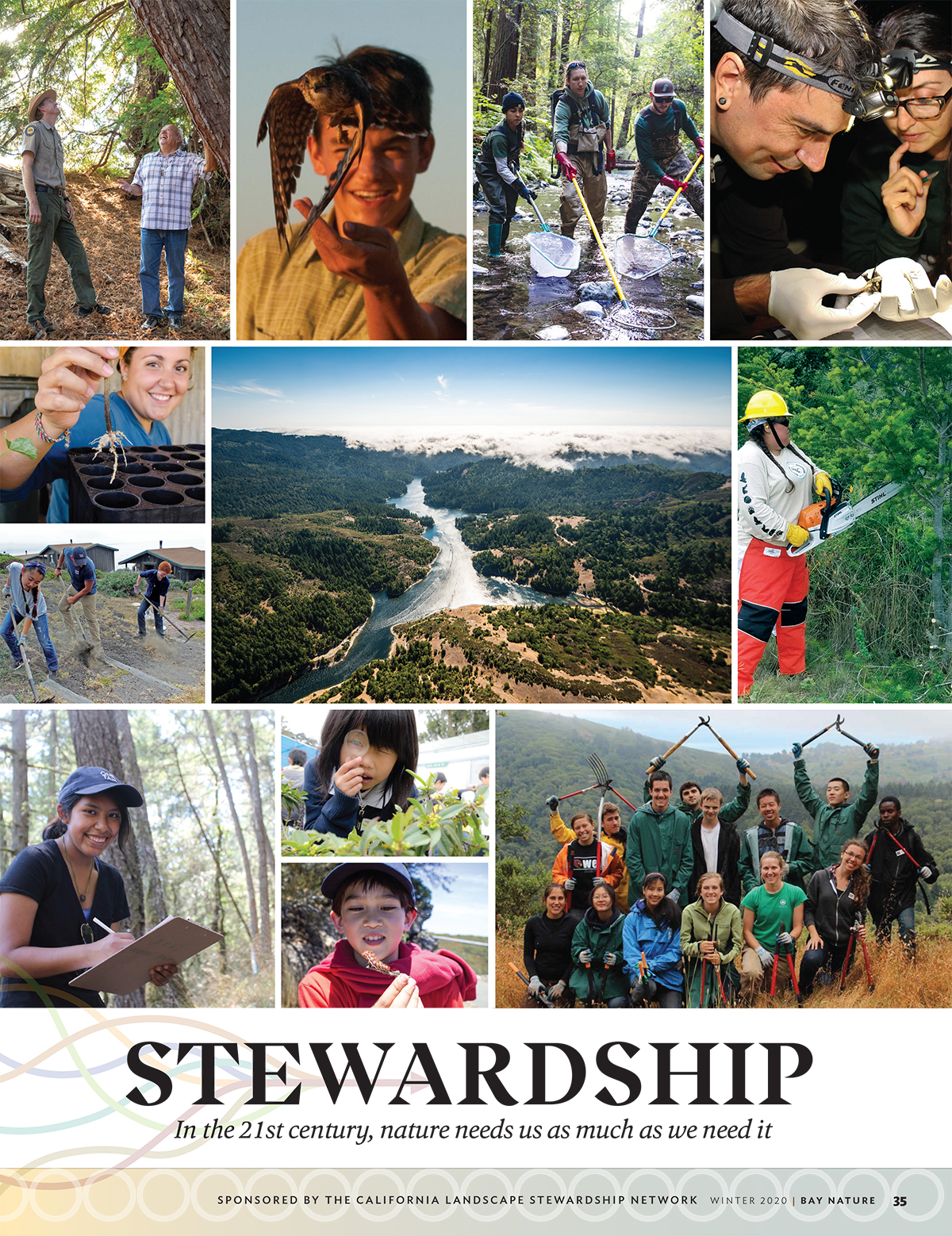

21st Century Stewardship

This series of stories sponsored by the California Landscape Stewardship Network explores the ways modern conservationists seek to define a new relationship with the natural world. Read more:

»What Stewardship Looks Like in the Santa Cruz Mountains

»One Tam’s Meteoric Rise in Marin

»One Tam: Bees Bring a Mountain Together

»One Tam: Where the Wildlife Are

In the 1970s, the mountain and its surrounding acres were protected by four agencies that control different pieces of the landscape—Mount Tamalpais State Park, Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), Marin Municipal Water District, and Marin County Parks. But by the turn of this century the challenges, inequities, and strain of four agencies with unique cultures and mandates all caring for a single mountain began to show. Mount Tam’s watershed, which spiderwebs across the landscape, is indifferent to jurisdictional boundaries. The salmon population was endangered, and Sudden Oak Death was killing tanoaks throughout the region. Invasive plant species were routinely removed in some jurisdictions but flourished in others due to lack of financial or human resources. When the California state parks financial crisis hit in 2011 and then-Governor Jerry Brown threatened to close 30 percent of the state’s public lands, including Mount Tamalpais State Park, the mountain faced an unprecedented situation.

The four agencies responded, along with the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, the nonprofit partner of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, by pulling together, and in 2014 the Tamalpais Lands Collaborative was born. The Parks Conservancy convened the alliance, enabling the agencies to explore ideas and challenges that affected the mountain’s ecosystems across boundaries. “The whole idea is that…we should be doing a better job of working consistently across boundaries to work on a landscape level,” said William Merkle, supervisory wildlife ecologist for the GGNRA.

As Sharon Farrell, with the Parks Conservancy, was helping partners launch the Collaborative, she reached out to the League to Save Lake Tahoe for advice. Founded in the ’60s, LSLT represents one of the oldest collaborative conservation efforts in California. And it had achieved something unusual, uniting an array of groups, including two state governments as well as federal and local organizations, to work toward a common goal. Farrell wanted to know how to do that.

Darcie Goodman Collins, CEO of LSLT, had this to say: Your messaging—the tagline that identifies your organization, in LSLT’s case Keep Tahoe Blue—matters tremendously. Keep it simple, punchy, and on point. And as you bring together a diverse group, some of whom may have competing agendas, focus relentlessly on your shared goals. “We’re all working to protect Tahoe no matter what sector we’re in,” Goodman Collins said by way of example. “Always come back to that commonality.”

The Tamalpais Land Collaborative struck on calling itself One Tam and developed an action plan called “One Mountain, One Vision” outlining plans for the first five years. The list of network projects included authoring “Measuring the Health of the Mountain,” a report that took stock of the mountain’s diverse habitats and species, with contributions from the four agencies and various scientists. Compiling the existing data was a two-year endeavor that built bonds between the agencies and revealed important information gaps. Those gaps guided their next steps.

One Tam has rigorously documented its efforts, publishing case studies for other networks to learn from. In six years it has become a model for a new era of collaboration and resource sharing in conservation.