This is an edited excerpt from Andrew Alden’s Deep Oakland: How Geology Shaped a City (Heyday, 2023).

Whereas the Hayward Fault, which runs the length of Oakland, perturbs us with energy from the Earth’s interior, Lake Merritt connects us to the world ocean, the world atmosphere, and the cosmic cycles of the solar system. Unlike the fault—invisible, inexorable, indifferent—the lake is open to all of Oakland, an intimate civic partner that registers and responds to every human touch. The landscape around Lake Merritt, near Oakland’s historical core, is rich with geologic features dating from a million years before the city was founded. Although a century-plus of human action has thoroughly changed the lake itself, the landforms around it are still plain to see.

Lake Merritt’s story is a combination of two stories, each a million years long: the repeated cycles of the sea during the ice ages and the steady rearrangement of the land by the Hayward Fault. Our lake is a world-class oddity, an arm of the Bay in the midst of a city. It rises and falls with the daily tides. An inside-out island, a marine habitat surrounded by land, it is truly a mediterranean sea. In Oakland’s early days it was a barrier, always in the way, but we’ve come to embrace it as the centerpiece of the room, framed like a sculpture, the city’s focal point.

But Lake Merritt is not really a lake. The early English-speaking visitors called it a slough—a tidal backwater with slow-moving currents and muddy banks—and named it for the Rancho San Antonio, the Spanish private land grant that once extended from Berkeley to San Leandro. Dredging has turned the San Antonio Slough to open water, but it remains an estuary, a brackish zone between fresh and salt water. Compared to lakes, estuaries are dynamic places, prone to waves and tidewash, cloudy with microscopic life and mineral nutrients, where a riot of species thrive in mingling waters.

The City of Oakland owns Lake Merritt. Its entire shore is a city park with attractions for people-watchers, bird-watchers, garden lovers, exercisers, and more. The geologist, ever attentive to landscape, notices that different types of terrain around the lake give it a visual rhythm, part of what keeps it so interesting.

On the map, Lake Merritt has the outline of a lower-case letter Y, defined by a long fat stroke slanting northeast–southwest and a short narrow stroke extending northwest to the mouth of Glen Echo Creek. But it’s important in geology to distinguish the human imprint from nature’s handiwork. The earliest good map of this area, published in 1857, shows the slough continuing southwest to the Bay in an open channel as wide as the rest of the lake. The long stroke of the Y was once twice as long as it is today. The slough’s natural shape is that of a person’s forearm, thumb raised as if to shake hands, truly an arm of the sea in a gesture of welcome. The wrist of this inlet is braceleted by the wide 12th Street vehicular bridge, a pedestrian bridge over the outlet channel, and the Lake Merritt Amphitheater. These human features now define the mouth of the lake.

The flow and ebb of tidewater past the scene is Lake Merritt’s daily breath. Its windpipe, so to speak, is the narrow channel to the Bay where the water can be seen rushing, in or out, at almost any hour. This place where land and sea and air converge is Oakland’s natural center, its shimmering heart.

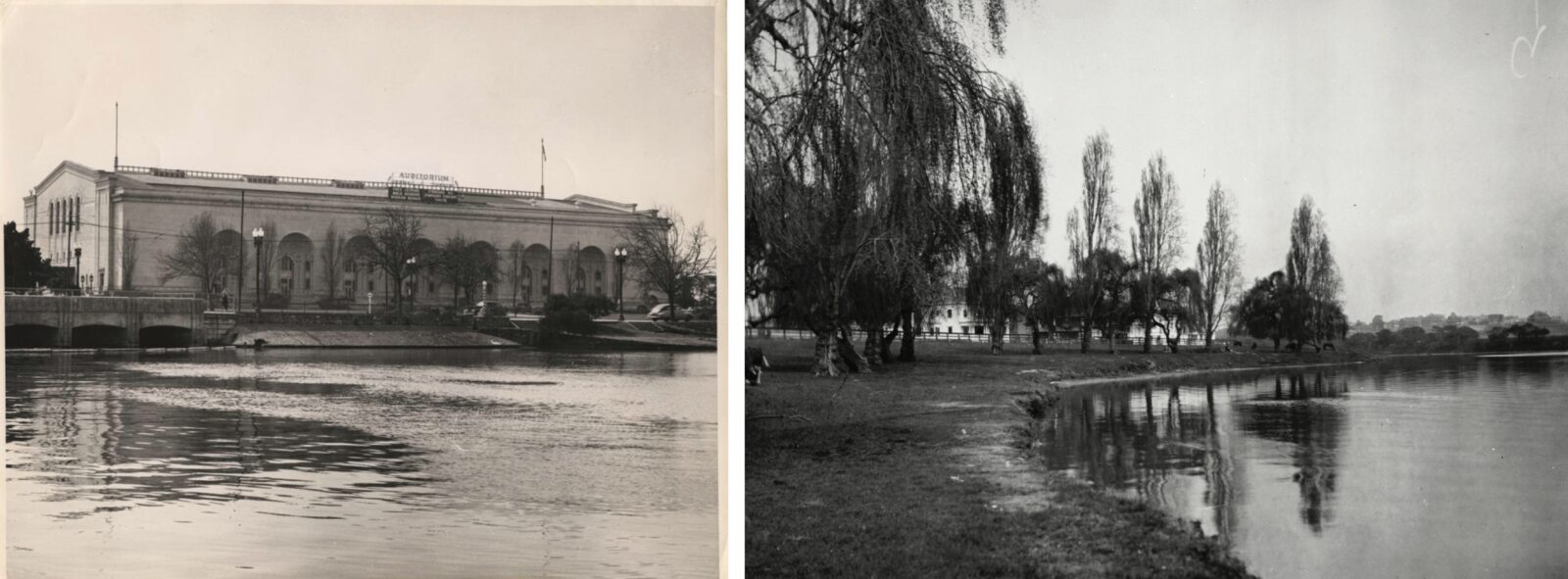

Downstream from the 12th Street bridge, the lake’s outlet channel snakes in a narrow trough. On the channel’s west bank, to the right, is the 1914-vintage civic auditorium next to the 1969-vintage Oakland Museum of California. Both buildings lie on landfill inside the original, natural channel shown on the old map. The original shoreline, the edge of the marsh, is visible farther to the right where 12th Street starts to rise near the museum’s back end. Atop the rise is the natural platform of downtown Oakland, around 10 meters in elevation; the county courthouse and neighboring landmarks stand on it.

The other side of the channel, on the left, is steeper and less obscured by buildings. Here the east bank rises to a platform of level ground, one that’s a few meters lower—a difference big enough to measure, but not enough to notice.

These two platforms, so much alike, have completely different origins. The downtown terrace is Oakland’s birthplace. It is made of windblown sand. Here I’ll focus on the other one, a marine terrace made of mixed sediment that accumulated under the sea. The terrace extends up the channel past the bridge toward the hills and sweeps around the shore.

Looking north over the lake from the amphitheater, we see the marine terrace on the right side, continuing nearly half a mile, past the white boat landing at the foot of East 18th Street, to the grassy rise of Pine Knoll Park. On the lake’s north shore straight ahead, the terrace makes up all of Adams Point, the wide, wooded shelf in front of Grizzly Peak that houses Lakeside Park. Out of sight on the left, it also flanks the narrow north arm of the lake. Everywhere the terrace is present, its flat surface and its abrupt edge are plain to see on the streets.

This terrace is made of clay and sand and gravel, topped with clay. It dates from a time in the recent geological past that was quite different from today. The shelf’s upper surface indicates where sea level once lay about 125,000 years ago. That was during an exceptionally warm break in the cycle of ice ages, when the global climate not only melted the great continental glaciers of North America and Eurasia but also shrank the ice sheets of Greenland and West Antarctica. The melted ice filled the sea some six meters above today’s high-tide level.

Today’s lake was then a wide, shallow bay. For perhaps a dozen thousand years, the Oakland streams flowed from the hills to this higher sea level and deposited sediment along the shore, where the tides swept it back and forth like a mason finishing a concrete sidewalk. Marsh vegetation took root and filtered from the estuary water a top coat of clay. The scene was lush; the low hills on the shore supported grazing and browsing animals that are extinct today. Then the glaciers reappeared, and gradually, as ice piled up on the continents, the sea shrank back and the terrace became land. Since then parts of the terrace have eroded, but much of it remains.

To put this age in perspective, recall that the Oakland Hills are roughly a million years old, a few million at most. To me, with my head firmly in geologic time, that feels like last week. The age of the terrace feels like last night.

Beyond the marine terrace, the far end of the lake is framed by low hills, friendly ones studded with dwellings and shops, rising steeply from the shore a hundred feet and more. They’re made of ancient river gravel and sand, cemented by mud and clay as firmly as sediment can be. The nearest bedrock is another mile farther away in the hills of Piedmont. These gravel hills and the more distant bedrock are two more puzzles, part of the million-year story told by the Hayward Fault. The lake, as the marine terrace has hinted, is a story told by the sea.

With that, let’s look more closely at the lake. Again, the first thing is to separate the human imprint from the natural landscape. The city dealt with this large, unavoidable natural feature in its midst by changing everything about it. During its human history, the estuary has been an asset or a problem, depending on the purpose it was put to and whether one considers the water or the shore.

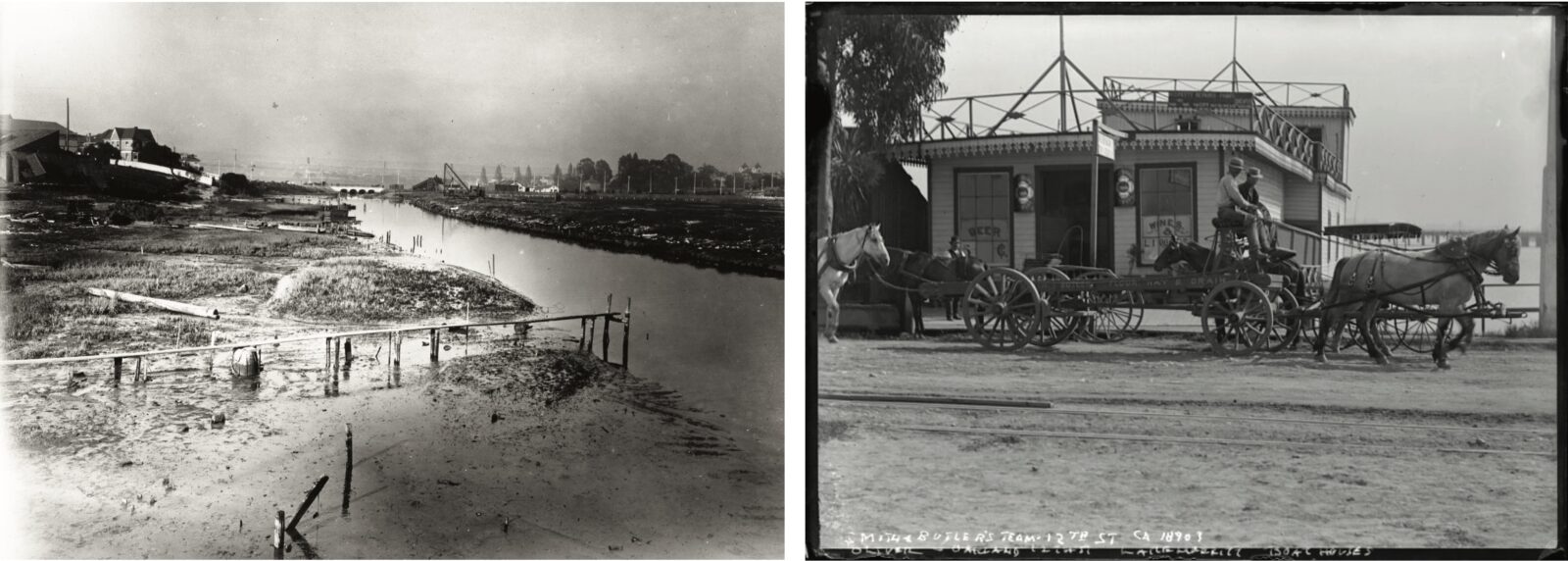

As a water feature, the slough was first a hunting ground and harbor for the Ohlones, who had a village at its eastern tip in Indian Gulch. During the Gold Rush, Americans came to the slough they sometimes called Laguna Peralta to hunt ducks. Access was easy enough for the Ohlones’ watercraft of bundled reeds, or a settler’s rowboat or small skiff, but only near high tide. At low tide the slough was a shallow channel surrounded by mudflats and marsh.

To the white people who settled this land, the slough was a barrier. The first Spanish expedition had to detour around it, irked by the steep hills and mosquito swarms at its eastern end. During the Mexican years, it slowed travel along the shore between the East Bay ranches. American settlers gathered in villages around two separate landings on opposite sides of the slough, San Antonio (soon renamed Brooklyn) on the east side in the 1840s and Oakland on the west side in 1850. Traffic between them was easiest by boat.

A few months after Oakland was incorporated in 1852, the town’s infamous founder, the squatter Horace Carpentier, built a bridge across the slough’s wrist. It was a toll bridge, naturally, that the citizens complained about bitterly, sometimes drawing pistols rather than paying the agent. That was the ancestor of today’s 12th Street bridge. More bridges were built nearby, for roads and for rail lines, and the lower half of the slough began to be filled in. Although both sides of Lake Merritt have been part of Oakland since the annexation of Brooklyn in 1872, it still marks the line dividing Oakland from East Oakland. Today, the interstate freeways bypass it on elevated roadbeds as if to avoid muddy feet.

In 1869 the mayor, Samuel Merritt, had a regulating dam built next to the bridge. The newly redefined lake immediately took his name. In 1870, Merritt pulled strings and had the state government quietly pass a law “to prevent the destruction of fish and game in and around the waters of Lake Merritt or Peralta, in the County of Alameda.” The law banished the duck hunters while leaving the shore open to human encroachment. Soon gracious homes began to rise on lakeside lots carved like steaks from the holdings of Merritt and other prominent men.

Oakland didn’t take Lake Merritt’s wildlife seriously for many decades. Meanwhile, the growing town’s untreated sewage fouled the water. An outlet tunnel built in 1876 carried the worst of it down 20th Street to the Bay. Around that time, the lake’s floor was gaining an inch per year of filthy mud. In the 1880s, when the city’s population more than doubled, sewage was linked to outbreaks of disease. In 1890, every doctor in Oakland signed a letter urging the city to drain the lake or fill it in. But the courts were still sorting out who owned the bottom of the lake.

When the litigation finished, in 1893, city leaders began to make Lake Merritt something more to their liking. Their projects changed the slough and its shore beyond recognition—except for the underlying geology. As the 20th century began, a dredging campaign turned the muddy slough into the basin of open water we know today. Proper sewage treatment helped the water heal, starting in the 1940s. A pumping station in the outlet channel started regulating the lake’s level, for flood control, in 1968.

None of these things were done for nature’s sake. For a long time, the city’s makeovers were human-centric. Firework displays were regular spectacles. Powerboat races in the so-called bird sanctuary began in 1927 and went on for 50 years. Old-timers remember them fondly. The lake served the city as an ornamental pool, just as the people and their leaders wished.

Then public attitudes toward wildlife began to change. More dredging in the 1980s helped remove decades of foul buildup. Aeration fountains were put in place, and public bonds funded massive renovations in the 2000s. The only boats allowed today are powered by sails, humans, or electricity. Now the lake—the estuary—seems to be doing better. The water smells good, the birds thrive, and we welcome our visiting guests from the sea. We know better how to work with the natural order.

The land around the lake, too, has been transformed in that time. In the 1900s decade, bond money bought out the lakeside estates, putting the entire shore in public hands, then the muddy margins were built up with dredging spoils. Along the eastern shore, a new street named Lake Shore Boulevard and a wide fringe of lawn were laid out on this landfill. Some spoils went into a little bird-nesting island in Lakeside Park, the first of what are now five. In the 1910s, the lake was lined with stone walls, backfilled with dredgings and broken rock from local quarries. Except for a small portion of Adams Point, the lake’s entire shore was armored until the renovations of the 2000s opened a few spots for marsh plants to return.

Along the slough’s outlet channel, landfill turned the wide, marshy passage into a tidal millrace. The newly made land was used to house a new campus for Laney College as well as the civic auditorium and the museum. In the 1950s, an amusement park beside the channel included a kid-size railroad line and a paddlewheel boat.

At Adams Point, the marine terrace was made over repeatedly as the city evolved. In 1850 an early settler named Romby dug clay there in the oak woods and manufactured bricks, as others did elsewhere on the terrace. Then it became the property of Edson Adams, second of Oakland’s three founding squatters. For a while it was a golf course.

The city acquired the Adams tract in 1907 to create Lakeside Park. Over the next 50 years, the flat ground filled up with attractions for every class of citizen—a beach, a boathouse, ball courts, and a bandstand; gardens, a large marble fountain, and an arboretum; a nature center, a duck sanctuary, and a geodesic dome; a pony ride, an amusement park, and a miniature railroad. The people loved them all.

Elsewhere, landfill transformed the head of Lake Merritt, where a large colonnade and pergola was built in 1913. The structure opens toward the lake’s outlet a mile away. East of the pergola toward the hills, landfill has turned the slough’s marshy tip into the wide grassy flat of Splash Pad Park, flanked by hills of ancient gravel and crossed by Interstate 580 on its concrete legs.

Several streams once came together at this flat, and the eye can follow their valleys toward the hills of the Piedmont crustal block. Pleasant Valley Creek comes down Grand Avenue on the left, and Wildwood Creek descends Lakeshore Avenue, as it’s called today, on the right, joining Indian Gulch Creek a block behind the freeway. Like other Oakland creeks, they now run in culverts beneath the roadway under round steel lids, although the heaviest rainfalls bring them erupting out.

In pre-settlement times, the streams were gradually filling the slough with mud and clay. Oakland sped things up by burying the creeks and finishing the job itself. Now the lake is firmly in human hands, but it was never static in nature’s hands either.