Amid the pickleweed and salt marsh at Palo Alto’s edge, southeast of the Dumbarton Bridge, is a 600-foot, U-shaped trail that doesn’t exactly scream “critical infrastructure.” But this modest path is actually a levee, holding back the ever-rising tides, and one of many such embankments that’s overdue for a lift.

“Right now, when the high tides come in, we’re about 200 feet from the water,” says Samantha Engelage, a senior engineer at the City of Palo Alto who works at the water quality control plant, near the trail. The plant is one of hundreds of critical Bay Area buildings—wastewater treatment facilities, runways, post offices—that are built right against the shoreline.

About this project: Bay Nature is reporting on funding for nature in BIL and IRA. Tell us what you think or send us a tip at wildbillions@baynature.org, and read more at our Wild Billions project page.

The city’s 2022 vulnerability assessment predicts that even a 25-year storm tide (as in, the kind you get once every quarter-century) would “overtop nearly the entirety of Palo Alto’s Bay shoreline”—while a 100-year storm would flood the Palo Alto Airport, the Baylands Nature Preserve, Highway 101, at least two schools, and large swaths of neighborhoods.

And that’s just in Palo Alto. There are about 540 Bay Area levee systems recorded in the National Levee Database, many of which are over 60 years old.

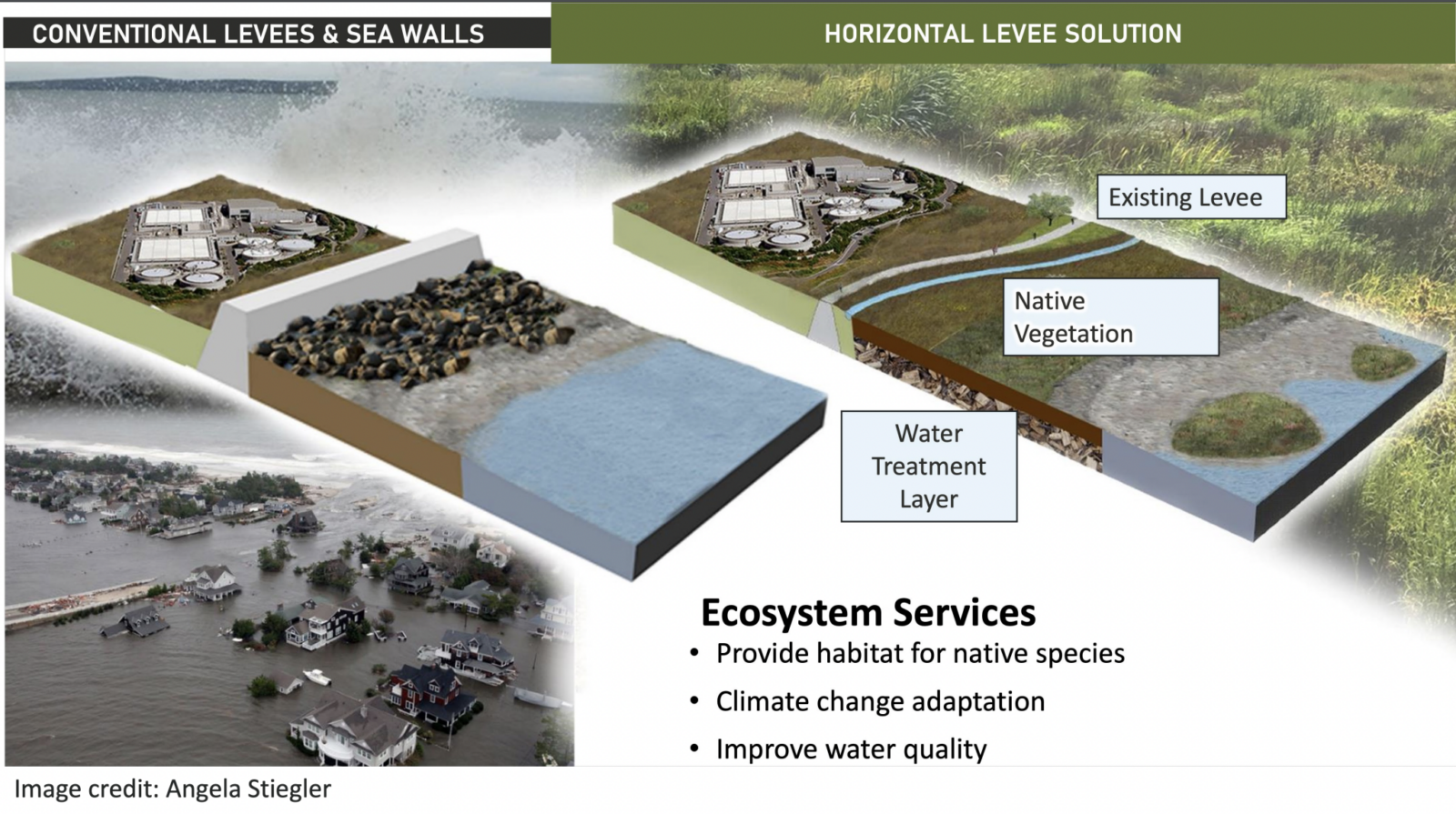

The old fix would be to raise the levee. Instead, the Palo Alto’s public works engineers are, like other governmental agencies and nonprofits in the Bay Area, pursuing a greener path: a horizontal levee. In a tiny, two-acre pilot project, they will push the existing levee farther inland and lift it. Then they will fill in and revegetate a gentle slope that leads from the levee down to the water. By doing so, they hope to put this little patch of liminal land to work on multiple fronts: attenuating the waves of rising tides, providing habitat for endangered animals, and helping further purify treated wastewater before it runs into the Bay.

The Palo Alto project’s design and construction is being led by the San Francisco Estuary Partnership, a collaboration of organizations and individuals dedicated to restoring the Bay, and has been funded with $4.3 million, via the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s San Francisco Water Quality Improvement Program, from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. It’s about 60 percent designed. Once it’s completed in 2024, it may serve as a model for revamping many more miles of existing, outdated levees in Palo Alto—and around the Bay.

Lost without a levee

The alternative is old-school—what people are now calling “gray” infrastructure: a tall concrete-and-earthen levee that walls off the salt marsh on the water side from any upland habitat, leaving it alone to fend for itself against the tide. North of this Palo Alto pilot project area (and in various places around the Bay), these kinds of levees are everywhere. Pursuing the same course here, Engelage says, would likely cause the salt marsh to disappear forever. As tides rise, existing vegetation would drown, and a mudflat would replace the marsh. Most of the Bay’s salt marsh has already disappeared due to human development.

For Julie Weiss, Palo Alto’s watershed protection program manager, that bleak alternative is rapidly becoming a reality. Weiss lives in Foster City, north of Palo Alto, where new levee improvements are being done using traditional means. She likens the construction to building a “big bowl of water” with a curving cement wall that will never be able to provide habitat to the creatures of the Bay.

“When I go out there now, in my backyard, I see a lot of riprap, and I see a big wall,” Weiss says. “And I imagine every single time I am out there, where are those birds going to go?”

The birds aren’t the only ones. The gentle slope of this new levee will provide refuge for at least two resident endangered species—the salt marsh harvest mouse and the Ridgway’s rail. Engelage says during high tide, the mice must cross the naked trail, exposed to eager predators, to escape the water. Meanwhile, Ridgway’s rails will often clump together in the uplands during high tides. But if a traditional levee were to be built, there would be no uplands for them to clump in—“except on a very, very narrow, steep edge of a levee,” says Julie Beagle, environmental planning section chief at the US Army Corps of Engineers, who has been working on how to help the Bay’s wetlands migrate uphill. “It’s really, really sad,” Beagle says. Without an upland refuge from high tide, “many of those species either are picked off, or predated, or are drowned.”

As it is now, the levee bisects the environment around it—splitting its section of the Baylands into two stark contrasts: a salty green marsh on one side, and a field of invasive weeds on the other. The refuge provided by the slope isn’t just a lifeline for the harvest mice and the ridgway’s rails, but for the marsh itself.

Now, we are asking more of the landscape

Historically, Beagle says, the freshwater uplands, supported by a healthy regional creek system, connected downstream with the saltier sections of the Bay, forming a kind of green gradient between the two distinct ecosystems. But as humans developed the land, freshwater became increasingly separated from saltwater. “Right now we have the levees and berms around the edge of the bay,” she says. “And so there’s these very clear dividing lines between like,

‘Here’s where people live, and here’s where the wetlands are.’”

By channelizing creeks to control overflows, we broke the connection between riparian habitats with their surroundings. Horizontal levees—part restoration, part flood control—seek to marry two priorities that were previously seen as conflicting, Engelage says. “We’ve made that decision over the years as a region to emphasize flood control over habitat. Now, we’re trying to see if we can do both,” Engelage says.

Fantastic levees, and where to find them

The hopeful seeds of the Palo Alto project—and its seed funding—originated across the Bay, near Hayward, at an experimental site known as the Oro Loma Horizontal levee, dating back to 2015, that was the first of its kind.

Funding left over from the Oro Loma site was also used to scope out new possible levee designs, and the Palo Alto project emerged from there, according to Heidi Nutters, a senior program manager at the Estuary Partnership. Meanwhile, at least 10 more are in the works or have been completed since then. This is a part of a broader strategy from SFEP to fund and design new projects one after the other.

“We’re trying to almost create this ‘snowball effect’—where the more projects we build, the more projects we can design,” Nutters says.

All over the Bay—from the completed Ravenswood Pond levees, near Alviso in the South Bay, to a still-in-concept project at Yosemite Slough in San Francisco’s Hunter’s Point—each of these projects has a different scope. Some, like the North Richmond Living Levee, connect to the Bay but do not transport treated wastewater. Others, like Oro Loma, are being used to purify water and provide habitat, but do not connect to the Bay.

The Palo Alto levee pilot, though, is all of the above. Human wastewater, even after treatment, is still rich with nitrogen, a nutrient that has lately been fueling major harmful algae blooms in the Bay. So to remove the nitrogen, treated wastewater from the wastewater treatment plant nearby will be piped over to the levee, and pushed out into a layer of wood chips. There, water and wood will stimulate microbial activity that breaks down nitrogen-containing waste—this is what makes it a “nature-based” purification process. On top, a layer of topsoil will support a bunch of vegetation, including riparian scrub and wetland plants like creeping wild rye, western ragweed, aster and arroyo willow. These plants can filter out some contaminants of emerging concern—chemicals like flame retardants or hormones that aren’t regulated like other pollutants but may still threaten humans, wildlife, and ecosystems. Whatever water the plants don’t take then eventually seeps from the levee into the marshland and then the Bay beyond, getting filtered along the way.

Out at the regulatory frontier

Since these kinds of levees are still experimental, their designers often have had quite the back-and-forth with regulatory agencies to get construction approved. “Permitting is really the biggest challenge to getting this idea to scale,” says Nutters, of the estuary partnership. The Palo Alto project’s managers have had to work with the nearby general aviation airport officials, who were worried it could increase bird strikes with aircraft. Often, project managers are balancing the competing demands of public access and endangered species protection.

Compared to other levee projects, though, permitting at Palo Alto has been a lighter lift—though it’s still taken six years to get this far. At least two other projects, in North Richmond and the First Mile Horizontal Levee, have encountered hurdles with wetland mitigation requirements, where the federal “No Net Loss” rule mandates that if sediment is going to be placed into an existing marsh, more marsh must be created elsewhere. “It’s been difficult for regulators to wrap their heads around and permit,” says Evyan Sloane, Deputy Regional Manager at the Coastal Conservancy. “To date, they require mitigation—instead of seeing the project itself as future wetland.”

Given that about a dozen of these horizontal levees are in development at the same time, their designers are also learning from each other as they go. So are the permitting agencies, which are starting to coordinate their reviews of such projects. Beagle says that compared to the guidance available for gray infrastructure—“thousands and thousands of documents on how to build seawalls and riprap”—nature-based solutions are brand-new territory for engineers and permitting agencies alike. What appears as a snag for one project will, hopefully, be a lesson learned for the next. “We’re hoping to make it easier for other projects,” Engelage says.