I hear the sound before I see it—a laughing trill, a liquid arpeggio running up and down. Then I round a bend and Wildcat Creek comes into view, its cool waters rushing and alive. My heart lifts. I feel as if I’m meeting an old friend after a long absence.

The thrill of finding the creek resurrected is all the more intense for my having witnessed its drought-parched streambed during a visit last summer. There was ample evidence of the creek’s passage: tree roots exposed, bedrock scoured. But water was scarcely to be found. To be clear, shrunken streams and golden hills are normal summer phenomena in our Mediterranean climate. But when rains don’t materialize for several years, there’s yin without yang—a delicate balance thrown out of whack.

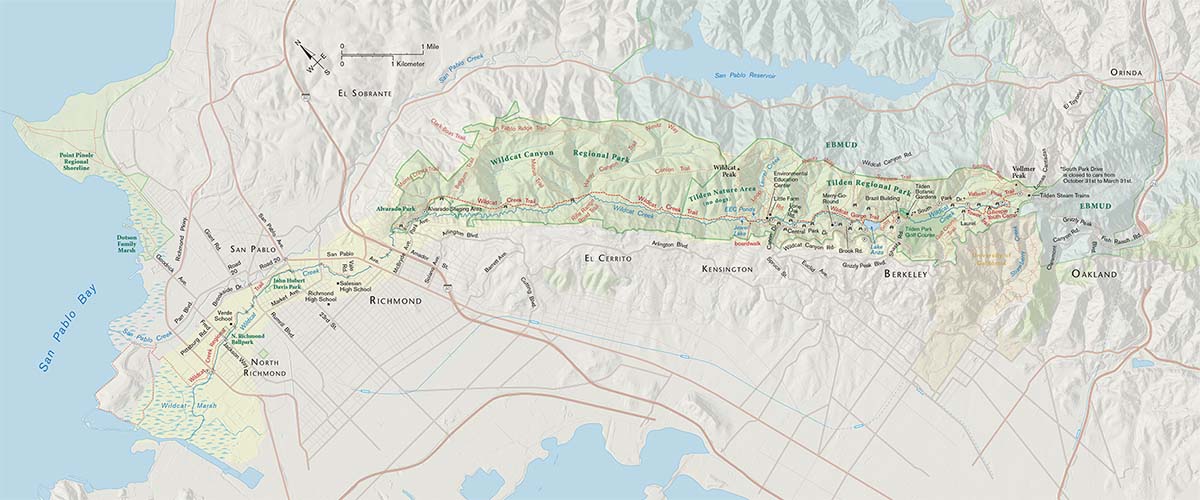

Now, “atmospheric rivers” have restored this balance and returned Wildcat Creek to its full glory. There’s no finer time to hike the upper course of the creek as it flows for 8.2 miles through Tilden and Wildcat Canyon regional parks in the East Bay. It’s a chance to experience this rich riparian zone at its springtime best and to gain a firsthand understanding of the ecological and hydrological forces at work in the Wildcat Creek Watershed.

Sara Fetterly, supervising naturalist at the Tilden Nature Area, believes that many visitors never stop to consider the outsize role that Wildcat Creek plays in the park’s landscape. “That’s why it’s so important for people to actually go out and follow the creek—see where the water flows, how it shapes the land and allows certain types of trees to grow. You can track the changes in animal and bird life, look for little invertebrates in the pools. The creek has so much to offer if you take the time to walk its banks.”

Wildcat’s 13.2-mile journey to the Bay begins on the slopes of 1,905-foot Vollmer Peak. The nascent creek wells up from beneath poison oak thickets near the Tilden steam trains, but bushwhacking to these inauspicious headwaters isn’t on my hiking agenda. I’ve come to Vollmer for the expansive views of the Wildcat Creek Watershed, which stretches northwest between San Pablo Ridge and the Berkeley Hills and then west across the alluvial plain to Wildcat Marsh and San Pablo Bay. It’s a challenge to wrap my mind around all the water that drains into the creek via this 11-square-mile catchment: rainfall, bubbling springs, urban runoff, fog dripping from the redwoods. The watershed is one massive equation and Wildcat Creek is its sum.

Descending Vollmer Peak Trail, I rendezvous with Wildcat Creek after it has taken shape and picked up steam, sluicing through the steep gullies near the Gillespie Youth Camp. It’s a lovely fern-lined stretch, though there’s no contiguous creekside trail to follow. I can only play peekaboo with Wildcat as it winds past various picnic sites and then disappears into the manicured Tilden Park Golf Course.

All along this stretch, the creek serves as a breeding ground for rough-skinned and California newts, which migrate by the thousands from upland summer habitats to their annual Wildcat pool parties. South Park Drive is closed to cars November through March to protect crossing newts from a squishy fate, and it’s a singular pleasure to stroll down the middle of the road, savoring the rare prioritizing of amphibians and pedestrians over automobiles.

At road’s end, Wildcat Creek crosses into Tilden’s Regional Parks Botanical Garden, stair-stepping through 10.5 acres of native California plants. I could easily spend hours here, sketching the delicate bells of blooming manzanita or watching for the scarlet flash of an Anna’s hummingbird. But that’s a creekside idyll for another day. Instead I continue behind the Brazilian Building to where Selby Trail connects to Wildcat Gorge Trail (the recommended starting point for this hike when South Park Drive is open to traffic and less pleasant to walk along). This uncrowded single track descends through eucalyptus stands that transition to bay laurel and coast redwood near the gorge bottom. Here Wildcat Creek greets me once again, tumbling out from below the botanic garden’s fence and racing through channels carved into the bedrock. I quicken my pace. Wildcat and I are on a roll.

Soon the creek spills out into Lake Anza, flowing past a great blue heron hunting patiently in the shallows. An earthen dam across Wildcat Creek created Lake Anza in 1938 as a water supply for Tilden’s golf course and a recreation destination for city dwellers. Today, Wildcat Gorge Trail traces the lake’s eastern shore, past rocky promontories overlooking the water—ideal places to exchange a kiss or scan for the playful river otters that sometimes travel overland to the lake. On the opposite shore lies a sandy swimming beach, a popular destination that’s suffered recent closures due to toxic blooms of blue-green algae (Cyanobacteria). Since 2020, EBRPD has used an oxygenation system to help combat the blooms, piping oxygen down to Anza’s 60-foot depths to aerate the sediment and suppress the nutrients on which the algae feed. Winter rains have also improved water quality, putting a spring swim at Lake Anza into the realm of possibility.

A song sparrow chirps above as I descend from the Lake Anza Dam along Wildcat Gorge Trail, which hugs the creek here for nearly a mile without interruption. This is a particularly stunning section, with mossy little waterfalls, a mysterious honeycomb of caves along the canyon wall, and a hollowed-out California bay laurel that offers a photo-ready hobbit hole. A riot of alder, bigleaf maple, and creek dogwood crowds the stream banks, while above, bay laurel branches form a perfect arch as they stretch forward to capture precious sunlight.

Visiting in the wet season, I’m struck by the damp, fecund smell and the long-missed squelch of mud that quickly turns my hiking boots into platform shoes. Pools that languished last summer are now brimming, providing habitat for myriad insects, amphibians, and fish. Native species such as rainbow trout and three-spined stickleback have evolved to wait out California’s seasonal droughts. “As the creek begins drying up, they sense changes in the temperature and the chemicals in the water and start to move to where they can survive,” Fetterly says. “The pools may be few and far between, but the fish know where to find them.”

Yet even well-adapted fish cannot surmount all obstacles placed in their path. Along the trail, an old concrete causeway crosses Wildcat Creek and connects to the Brook Road parking area. “Rainbow trout can’t swim up the concrete crossing,” says Joe Sullivan, EBRPD fisheries program manager. He describes an upcoming restoration project, scheduled for 2023, that will remove the concrete blockage, install a pedestrian bridge over the creek, and create a fish riffle that the rainbows can navigate. Removing migration barriers all along Wildcat Creek is part of Sullivan’s ambitious long-term vision to bring back steelhead—seagoing rainbow trout that return to their native streams to spawn—to Wildcat’s waters.

Mitigating the past and present impact of humans seems to be an ongoing task for the creek’s stewards. Says Sullivan, “One of our main focuses in Wildcat is to keep people out of the stream.” He notes that hikers sometimes follow bootleg paths to the water’s edge, trampling vegetation and contributing to streambank erosion. Off-leash dogs are a particular problem. “They see a pool or catch a scent on a game trail and make a beeline to the creek,” Sullivan says. “We’re talking hundreds of dogs a day.”

Such relentless erosion is undesirable, and yet creek-borne sediment also serves a beneficial function, delivering vital nutrients and replenishing habitats. “It’s important to recognize that creeks are corridors of conveyance for both water and sediment,” says EBRPD civil engineer Scott Stoller. “There’s a dynamic equilibrium in a natural watershed, where sediment that’s eroded from one place is deposited in another.” Stoller explains that when dams halt this natural process, they create “hungry water” downstream—sediment-starved water that scours streambeds and diminishes aquatic habitats. As I’m learning with each footstep, so much in the watershed comes down to maintaining balance.

The creek and I part ways again as Wildcat Gorge Trail terminates at Lone Oak Road. I pick my way along the shoulder and through a parking lot, joining young families headed to the Tilden Little Farm. Soon I find the creek again, flowing beneath the broad wooden bridge that leads to the farm and Tilden’s Environmental Education Center. The EEC provides a good halfway-point pit stop for hikers, with restrooms, maps, and fun interpretive displays, including a diorama of the Wildcat Creek Watershed that shows how its crenellated canyons funnel water to the creek and eventually the Bay.

But today I’m too eager to reach Jewel Lake and witness the transformation wrought by winter rains. I set off down the Wildcat Creek Trail fire road, then detour left along the accessible boardwalk that zigzags through willow thickets and passes several dusky-footed woodrat nests—large stick-and-bark assemblages that suggest an Andy Goldsworthy sculpture.

Finally Jewel Lake comes into view, its resurrected waters broken only by a wintering pair of black-and-white bufflehead ducks. The tranquil scene is a far cry from last summer, when the lake had shrunk to a mud puddle and I watched as wasps fed on the silvery bodies of invasive mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) trapped in the muck. A small boy had approached with his mother, asking her repeatedly, “Where did the water go?” The answer is a complex combination of the summer season, prolonged drought, and ongoing sedimentation from Wildcat Creek, which creates an ever shallower lake prone to vegetation and evaporation.

What does the future hold for Jewel Lake? The EBRPD Board of Directors is currently considering the path forward, which involves choosing between four different restoration concepts. Two involve relinquishing the artificial lake: one by allowing Jewel Lake to continue its transition to a marshy meadow, the other by removing Jewel Dam and restoring Wildcat Creek to its original channel. Two other concepts maintain Jewel Lake, either by periodically dredging the lake bed (while adding a fishway around the dam) or by rerouting Wildcat Creek to bypass the lake, with a channel to divert water into the lake when creek sediment is low.

“There are good arguments on both sides of the fence,” says Fetterly of the difficult choice. “What speaks to me is the science. Looking at the effects of dams and non-natural lakes and ponds, the question is ‘ethically, is it good for the environment?’”

After careful study, deliberation, and public input, the board will announce its preferred concept this spring. “No matter what happens, we’ll have an amazing place,” Fetterly says. “A place that supports native species, that includes interpretive programs, and where people can seek solace in nature.”

Such a destination already exists on a smaller scale at the new EEC ponds just east of Jewel Lake. The three seasonal ponds were constructed as an interpretive feature and a vital habitat for native species. Half-submerged logs provide easy exits and sunning opportunities for western pond turtles, while the shallow depths play to the strengths of California red-legged frogs. These drought-adapted frogs mature quickly, whereas predatory American bullfrogs can take two or more years to undergo metamorphosis. When the ponds evaporate in summer, the native frogs have already developed lungs and moved on, leaving the invasive bullfrog tadpoles high and dry.

From Jewel Lake, I follow Wildcat Creek Trail for less than a mile to where it crosses Tilden’s border and passes into Wildcat Canyon Regional Park. If Tilden, with its people-pleasing picnic sites, playground, and carousel, is the social butterfly, Wildcat Canyon is the moody maverick, rugged and untamed. Here the landscape opens up into wide, exposed grasslands, with red-tailed and Cooper’s hawks riding the thermals. Mule deer, turkeys, gray foxes, and coyotes roam the rolling hills, along with the seldom-sighted bobcats and mountain lions that may have given Wildcat Canyon its name.

Cattle also graze the hillsides, keeping the European grasses in check—a reminder of the vast Spanish ranchos that once laid claim to this canyon. The Spanish reached the mouth of Wildcat Creek in 1772 and were met by Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone, who occupied thriving villages on San Pablo Bay. Ohlone fished, foraged, and hunted along Wildcat Creek and maintained the canyon’s open grasslands by setting fires in the fall. Chochenyo-speaking tribal members live in the region today and some have been consulted on the restoration plans for Jewel Lake, which lies within their ancestral homeland.

Hiking the last three miles of Wildcat Canyon Trail, you can see the forces of the watershed on full display, as smaller tributaries drain down from the emerald hills and join the Wildcat Creek conga line as it dances toward San Pablo Bay. The streambed itself is seldom visible, though a telltale ribbon of alders reveals its course to my left. At several points, narrow paths cut through the underbrush toward the creek, but I resist the temptation, the impact of erosion fresh in my mind.

Instead I admire the profusion of trailside mushrooms that sprout like conversation bubbles from the leaf litter. Winter rains have invigorated many moisture-loving species in Wildcat Canyon, from the delicate turkey tail found on downed logs to the brown, saucer-size Tricholoma dryophilum,aka oak-loving trich, so-named for its symbioticrelationship with the coast live oak that dominate the park.

Soon the dirt trail shifts to pavement, eventually becoming wide enough to land a jet plane. This bizarre asphalt boulevard—marked as Wildcat Canyon Parkway on some maps—is all that remains of plans for an intended housing development, abandoned in the 1960s. Reaching the finish line at the Alvarado Staging Area, I give thanks to the planning gods that this spectacular canyon was spared.

My eight-mile traverse of the upper watershed is complete, but there’s still something left to do. I continue into Alvarado Park, where once again the creek comes into view, winding past picnic areas and ducking beneath a WPA-era stone bridge before disappearing around an ivy-choked bend. I stand on the bank and bid adieu to the trout-filled, tree-sustaining, sediment-bearing waters. I wish Wildcat well on its journey.

Explore: Wildcat Creek

Upper Watershed

»Trail maps for Tilden and Wildcat Canyon regional parks are available online.

»South Park Drive is closed to automobile traffic annually from October 31 to March 31. At other times of the year, use caution when accessing this portion of Wildcat Creek, or consider starting your hike at Lake Anza.

»This point-to-point hike requires dropping off a car at one end or hailing a ride share (or a good friend).

Lower Watershed

Past Alvarado Park, Wildcat Creek’s adventures continue for another five miles through San Pablo, Richmond, and North Richmond before ending with a splash at San Pablo Bay. The creek once meandered freely across this alluvial floodplain. But as the area urbanized, the streambed was subjugated by concrete channels, buried in underground culverts, and bisected by railroad tracks and Interstate 80. Like Rodney Dangerfield, Wildcat couldn’t get any respect.

Thankfully, local agencies and nonprofits have worked to restore sections of the lower watershed—“daylighting” underground portions, rebuilding aquatic habitats, and promoting native fish passage. The Wildcat Creek Restoration and Greenway Trail Project was completed in spring 2021, with almost a half mile of streambed “naturalized” to create a park-like pedestrian corridor through the city of San Pablo. Similar efforts are underway in unincorporated North Richmond. Here, young interns with the nonprofit Urban Tilth work to propagate native plants, remove invasive species, prevent erosion, and engage their communities.

“We want to make it possible for people to contribute to something bigger,” says Juliana Gonzalez, executive director of The Watershed Project, an environmental education nonprofit that invites volunteers to help measure the creek’s water quality and assist in trash assessments—not just picking up trash, but sleuthing down its source. Little by little a path to the Bay is being stitched together.