To hear Roger Castillo tell it, all of the City of San José—its million inhabitants, its sprawling residential neighborhoods, its glittery glass high-rises and office-park tech campuses—is more or less floating around on the backs of a bunch of salmon.

Jump to the map

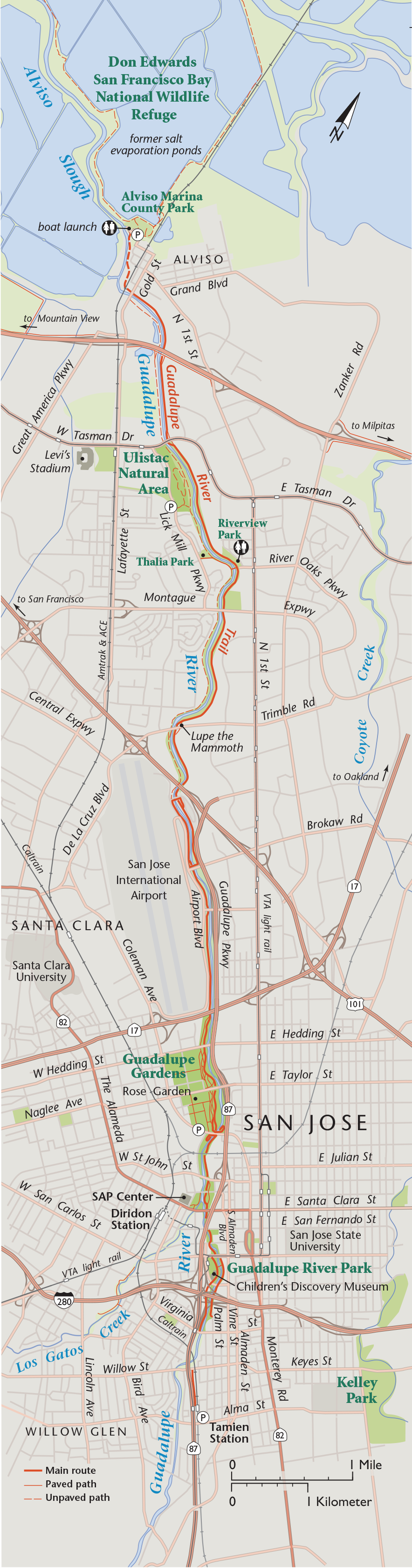

Trace the path of the Guadalupe River along cartographer Ben Pease’s 2018 map for Bay Nature.

This is not so implausible as it sounds. San José is a river city, split neatly from north to south by the Guadalupe River, a 14-mile waterway that can flood with 14,000 cubic feet per second of water in the winter and shrink to mostly dust in the summer. Over the years the water that flows inevitably from the hills and reservoirs in the Santa Cruz Mountains northward into the San Francisco Bay has been diverted into culverts and storm sewers to tame the river’s once vast, wandering path. But the water flows nonetheless. And where there is flowing water, there might be salmon.

Castillo describes times of wading hip-deep through the underground storm sewers of the city, amid a thousand juvenile salmon fry. A monster fish he rescued from a pump station near Great America is now taxidermied and hanging on the wall in his small office; in 1996 he caught a 30-inch Chinook in a drainage channel near the Norman Y. Mineta international airport. (“People don’t know the airport was built on top of the river system,” Castillo told me. “In wet years, the runway floats.”)

Castillo, a lifelong San José resident, semi-retired semiconductor assembler and forklift driver, and recent board president of the Guadalupe-Coyote Resource Conservation District, took me a few months ago to a spot where Highway 101 runs through a deep road cut just east of Interstate 880. Tenth Street crosses over this, and from just on the shoulder of the overpass, Castillo dropped to his knees over a storm drain leading into a gushing sewer. I found it physically disorienting in an M.C. Escher sort of way. Like, you are standing looking down at an open eight-lane freeway of rushing cars two stories beneath your feet and then somehow also peering down six feet into a sewer full of rushing water where, Castillo says, he saw several dozen baby salmon just last week.

People ask, and argue, about what it means that there are imperiled fish living in the San José sewers, says Castillo, but at heart it’s simple. It means that where water flows everything is connected. In his head Castillo carries a map of the entire network: The old river and its pathways, the new river and its drains and ponds and pumps and how it is all one big web of interconnectedness. The historical ecology of the Guadalupe River is never far from the surface.

This spring, I decided to hike and bike San José by following its river. I started by walking north from the Tamien Caltrain station, where quiet suburban pocket gardens overlook the river. At West Virginia Street the beginning of the Guadalupe River Trail is commemorated with a salmon bas-relief on a bridge and a sun-shape cut into the base of a balcony overlook.

A shady hiking and biking trail leads north along the riverbank for about a quarter-mile through a eucalyptus grove. As you approach the Highway 87–Interstate 280 junction, the river enters a constricted channel that also marks the river trail’s unofficial entrance to downtown. The pillars of the freeway overpasses sprout like giant trees, and the calm water meanders through this shady forest, reflecting a sort of shimmery concrete white.

Historically this stretch of the river was the heartland of the Tamien-speaking Ohlone, and it passes through what once would have been a vast freshwater meadow fringed by several miles of sycamore groves and a dense willow forest now named, unsurprisingly, Willow Glen. The Guadalupe once began in this willow grove, merging several smaller creeks, springs, and wetlands that then flowed north with the more forceful intent of a river. “It is no coincidence that San José is located immediately north, just downstream of the perennial water that emerged from Willow Glen through the Guadalupe River,” wrote Erin Beller, Micha Salomon, and Robin Grossinger, historical ecologists at the San Francisco Estuary Institute, in a 2010 report about the history of the West Santa Clara Valley waterways.

These former meadows were rich agricultural land, and the first instinct of white settlers was to drain the swamp, plant agricultural crops, and build levees to prevent the river water from coming back. Subsequent generations continued to tighten the straitjacket.

San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research (SPUR) San José Director Teresa Alvarado grew up in San José just down the road from here and says she first noticed the river the way a lot of residents did back then—when it flooded. In March 1995 a massive storm led the river to overtop its banks. A pool formed along the Highway 87 embankment downtown. A Water District report measured a flow of 9,000 cubic feet per second under the St. John Street bridge. “We could not travel east on our street because of the floodwaters,” Alvarado says. “That was the first time I was aware of the river, and it blew my mind.”

After those floods the Santa Clara Valley Water District and the Army Corps of Engineers spent two decades rebuilding the edges of the river, widening the channel in many places to increase capacity and support a more natural river system. Now, as that work nears completion, people have caught on to visions Castillo, Alvarado, and many others have put forth to bring the Guadalupe back to prominence.

River advocates see the period of rapid development and transportation investment downtown as an opportunity to capitalize on the river’s new edge and to revitalize the once-and-future natural heart of the city. “We want to create a place that’s a central green space in San José, that’s built for people, that gives people an opportunity to connect with one another and with nature,” says Alvarado, who is working with San José Mayor Sam Liccardo on a new design vision for the Guadalupe and downtown. “We want to create a central focal point, a stronger sense of place for San José.”

San José was one among many cities to successfully pave and forget its river in the 20th century. Los Angeles did so too, but on a much larger scale. In Los Angeles, as major restoration work began to bring the 51-mile L.A. River back to life, a UC Berkeley team led by Marcia McNally surveyed people who lived near the river. Only 31 percent said they knew it was there. But in Studio City, where the edge of the river had just been turned into a natural park, the number of people who knew about the river jumped to 78 percent. River parks, McNally concluded, could both create a reminder of nature and improve community health.

San José’s Guadalupe River advocates, particularly SPUR’s design group, watched and learned from Los Angeles. SPUR has since conducted its own surveys among San José residents. Support for revitalization is high, but only 37 percent say they’re proud of the river. “They don’t feel proud of it as it currently is, but they do feel invested in the future of the park,” Alvarado says.

One reason people still shy away from the river is obvious. This neglected space through the city’s core is also where booming Silicon Valley pushes the societal injustices it wants to ignore. San José estimates more than 4,000 homeless people live in the city, and many of them make a life along the river. Walk or bike the trail, and you see tents under every overpass. Makeshift shelters grow thick in the willows lining the east bank of the river near downtown. It is clearly an environmental concern: Roger Castillo told me he sees homeless people poaching salmon and disturbing redds, leaving trash in the river, and digging into restored banks. Others told me people avoid the river because they fear the encampments. The 2017 SPUR survey showed that members think the Guadalupe River Park & Gardens, which cover the two miles from the Children’s Discovery Museum north to Hedding Street, is the most unrealized gem in the city; solving the homelessness problem there was by far the members’ highest concern.

You can only ignore the presence of the homeless along the upper Guadalupe River if you ignore the river itself. It works backward, though: Now that more people are paying more attention to the river, the extent of the problem in San José becomes inescapable.

“By placing all of these people into the hidden reaches of the waterway, it really masked the severity of the problem we had in homeless population numbers,” says Steve Holmes, the executive director of the South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition. “The creeks are a subset of a larger problem, the homeless problem, but why can’t we have better streams and housing for the homeless?”

Castillo, as we drove around, echoed the same thinking. “I’m finding all these miracles, but meanwhile the city is using the streams to hide social problems,” he said. “I’m running around trying to save this river system, but we’re using the river system to house people.”

There is no obvious answer here, no particular wisdom from the river. But the river is a reminder that nature connects everything and that restoration projects are as much about people and our society as they are about fish.

The river runs along a deep, narrow channel through downtown. But for the tenth largest city in the country, downtown is deceptively relaxed. In one spot near West San Carlos Street, I stopped to watch a merganser paddle in the shade of a California bay laurel. It is surprising to contemplate the natural placidity of the ivy-tangled banks, the water and the ducks, and think of the human energy all around: The riverside park meanders around grassy lawns past the Children’s Discovery Museum and the San José Center for the Performing Arts. The Convention Center, on the east bank, was hosting the F8 Facebook developers conference; SAP Center, on the west bank, was hosting a San José Sharks playoff hockey game.

I walked along the flood-protecting, restored bank of the river, decorated with cutout salmon art, under banners celebrating San José’s Little Italy. I passed the Piazza Piccola Italia. Then I crossed to the east bank, where bike paths dance north through a forest of sycamore trees, to the city’s historic orchard, heritage rose garden, and river-themed children’s Rotary play garden.

On signs dotting the riverwalk, the city labels the Guadalupe River Park & Gardens as a “2.6-mile-long oasis of discovery, peace and pleasure.” It is close to achieving that feel. Since the main park opened in 2005, additional pieces have come online, like the Rotary play garden in 2015. Now that the park exists, Teresa Alvarado says there’s another lesson to learn from Los Angeles. “How do we enhance what’s happening,” she says, “but really pump up the volume and call attention to the fact we have an urban river there in our midst?”

Alvarado imagines the parks with live music, outdoor events, and festivals. “When they step off the high-speed rail or Diridon, we want to see folks walking around,” she says. “You want to hear music, see young people doing whatever they’ll be doing in 10 years—hovercrafting. You want to see a place that feels fun, invites people to be creative. You want to hear laughter.”

And, as Castillo has always emphasized, you want to see fish. You want to know about the beavers that returned to live in a pond downtown, and the dozens of species of birds that rely on the river’s riches. For Stephanie Moreno, the executive director of the Guadalupe-Coyote Resource Conservation District, community interest will follow as ongoing restoration and investment increases. “If the river supports fisheries again, it naturally supports other wildlife and makes it healthier for people who want to recreate,” she says. “I wish we could get more corporations interested in the river. It’s a quality of life issue, and for their employees to have a healthy river system they could walk along, bike along, paddle down—it’s a different dimension than being in a concrete jungle.”

North of the park and gardens I picked up a rented bicycle to navigate the next seven miles of the Guadalupe River Trail. A continuous paved pathway, opened to the public in 2013, connects downtown San José to the Alviso Marina and the restored wetlands beyond. From Hedding Street and the end of the Guadalupe River Park & Gardens, the river runs north for about three miles past the airport, then under Trimble Road, where Castillo had shown me one of his most special sites.

Santa Clara Valley Water District controls the release of water through the river’s many pumps, and Castillo compares following its rhythms to watching a heart monitor. On a summer day in 2005 he saw what looked like cardiac arrest and went down to the river to explore. A massive water release had scoured the bank and exposed some animal bones. Castillo called a geology professor, who in turn called the assistant director of UC Berkeley’s paleontology museum. Excavations over the summer turned up a femur, pelvis, toe bones, rib bones, and part of the skull of a juvenile Colombian mammoth. The bones are on display now at the Children’s Discovery Museum, and a silver mammoth statue guards the Trimble Road bridge over the river.

Right around here the river picks up a tidal influence from the Bay and, on a typical day, a sea breeze. The river trail swings with the waterway past low corporate offices and apartment complexes and grows crowded at lunchtime with walkers and bikers. A mile and a half north of the mammoth you reach the best stretch of the trail for natural history lovers. At Riverview Park on the east bank, a bike and pedestrian bridge crosses over into Santa Clara at the site of the onetime mansion of wealthy 19th-century businessman, land baron, and science patron James Lick. From there it’s another three-quarters of a mile to the Ulistac Natural Area, a 40-acre refuge of native plants, birds, and butterflies.

A ramp drops down from the levee into the natural area and immediately you’re in among California sagebrush and flowering buckeye. Mockingbirds and woodpeckers dart through the canopy and a variety of butterflies patrol the flowering meadows, while giant tiger swallowtail butterflies flit through sun and shade. Parallel trails lead through Ulistac for about a third of a mile before rejoining the Guadalupe River Trail on the unpaved west bank.

The river itself grows wider and marshier as it nears its mouth, although nothing like what it once was. Two centuries ago the Guadalupe spread into a vast wetland fringing the Bay. It would have been hard to pick out the main channel amid acres of dendritic outlets. You can still get some feel for this by continuing past the end of the Guadalupe River Trail and into the restored salt ponds of Alviso.

But I chose to stop where the river trail did. At the edge of the Bay I turned away from the sea breeze and pedaled it all in reverse: past soccer fields and apartment complex pools and a cormorant surveying the lower river from a wire, past the 49ers stadium and the Ulistac Natural Area and the mammoth discovery site, past the airport and the jail and the heritage park, past the rose garden and the tent camps and the hockey arena, past the skyscrapers and the museums and the freeway interchanges, to the train station.

For all the individual things to see along the way, it was ultimately that final 10-mile ride that I found maybe the most remarkable piece of the whole day. You can traverse, without stopping, 10 miles of a city built to be navigated by car. Driving across the city is inconvenient now, a story of stops and starts and impediments and missed connections. Meanwhile nature has resurfaced, and in a few hours of following the water you chart the complex and diverse systems of the South Bay: geographic, social, environmental. The Guadalupe River, as we sometimes need reminding that rivers did and do, brings the big city together.

Trace the Path of the Guadalupe River

Map by Ben Pease, 2018.