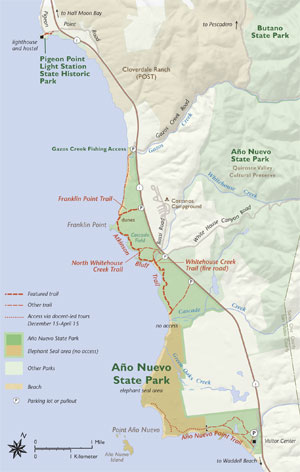

On a deserted weekday afternoon, this sliver of Año Nuevo State Park feels fixed and immutable even as the wind and waves blow and break. West of Highway 1, the land slides from shifting dunes into prairie and scrub and then drops off precipitously, exposing ocher-colored bluffs that meet the Pacific. Brown pelicans glide by overhead and young male elephant seals hump from the surf onto crescents of beach in small coves. Just a few miles north of the popular elephant seal rookery, the landscape appears all but untouched save for a narrow, unsigned stretch of the California Coastal Trail (CCT).

That 1,200-mile trail from Oregon to Mexico, whose completion is mandated by California law, threads through the northern coastal sector of the park. The two-and-a-half-mile Atkinson Bluff Trail doubles as the local segment of the CCT, and it was called “magical” by two California Coastal Trail Association ambassadors who raised awareness for the trail last summer by hiking and biking its length. “The sight of dune flowers in full bloom against the teal sea … soothed our souls,” ambassadors Morgan Visalli and Jocelyn Enevoldsen wrote.

I decided to check out this part of the trail on a recent warm fall day. To reach the northern end, I parked at an unmarked dirt turnout off the west shoulder of the highway, about a half-mile north of Rossi Road. The signed Franklin Point Trail runs perpendicular to the pavement, heading straight toward the shore less than half a mile away. I was joined by Toni Corelli, a botanist who knows the coast; she lives blocks from the beach in Half Moon Bay to the north. Together with colleagues from the Coastside State Parks Association and California Native Plant Society, she coauthored the 2013 book Plants and Plant Communities of the San Mateo Coast, a spiral-bound, full-color guide to the region’s flora.

“This is a unique area,” Corelli says, “because it’s so separated from Highway 1.” In few places between San Francisco and Santa Cruz is there so much protected land west of the highway. Our plan is to hike from the car to the rocky outcropping at Franklin Point, south along Atkinson Bluff Trail near to where Whitehouse Creek spills into the Pacific, then east along the South Whitehouse Creek Trail toward a second car: Barely more than a mile as the crow flies, and fewer than three on foot. “Here you have this amazing biodiversity, some 400 species of plants—both native and nonnative,” Corelli says.

After walking along a sandy singletrack up and over the first in a series of rolling back dunes, we find ourselves approaching an almost imperceptibly shallow depression in the land. At my request, Corelli begins naming names. Arroyo willow, she says, brushing her fingers over elongated leaves. Western goldenrod, whose yellow flowers are among the few still blooming in mid-October. These are wetland indicator plants, suggesting, along with the topography, that water is not far beneath our feet.

“Juncus lescurii,” says California Native Plant Society member John Rawlings, who has also come along for the walk. The stiff, dark-green stems of San Francisco rush grow in intermittent stands along the path. The plant brings a textural richness to the landscape with its cylindrical stems and tidy bunches of brown to yellowish flowers, emerging along the length of the stalk rather than at the top. In fact, the upper half of the stalk is technically a scale, or modified leaf, that looks almost identical to the stem below.

“Rushes and sedges and grasses are really conspicuous elements of the coastal habitat,” Rawlings says. (I’m reminded of the mnemonic “Sedges have edges, rushes are round, and grasses have joints.”) “They’re not showy in the way that some other monocots are,” he adds, “and often people don’t notice them because they all just look like green grasses.”

San Francisco rush grows along much of the immediate California coast and potentially as far north as British Columbia, in both fresh and saltwater marshes, on the shores of creeks and lakes, and even atop beach dunes. A perennial that spreads vegetatively via rhizomes, it grows to three or more feet in height. Some other local rushes (there are about nine here), like toad rush, are diminutive annuals, meaning they must set seed every year to survive and are more susceptible to displacement by invasives.

We follow the San Francisco rush through the riparian zone over a succession of foredunes toward a calm cove where the ocean meets a sandy beach. (For those who want an uncrowded broad stretch of beach to walk, head north from here.) Along the way we pass beach strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis), a native to the Pacific coast that has been distributed as far as South America by migrating birds. The plant, which bears a tasty fruit, is also a parent of the garden strawberry we commonly eat. In the 1700s F. chiloensis accidentally hybridized with another strawberry and we’ve been cultivating the offspring ever since.

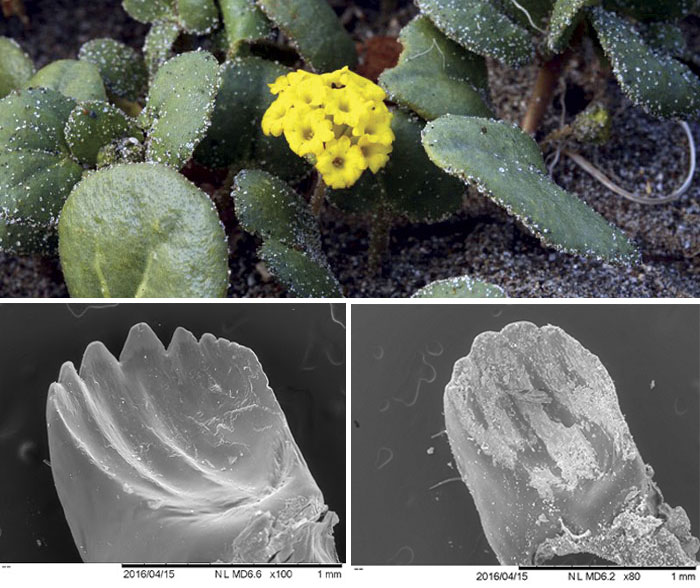

Corelli also points out yellow sand verbena (Abronia latifolia), an herb snaking across the sand that bears bunches of small yellow flowers from March through October and is conspicuously dusted with sand that clings to the plant’s sticky hairs. A lot of plants entrap soil this way, and a study of A. latifolia revealed that the gritty sand helps deter the hungry caterpillar of the white-lined sphinx moth (Hyles lineata) from eating its otherwise succulent leaves. Eventually a caterpillar will eat the sandy bits of the plant, but at the cost of grinding down its sharp mandibles.

Not all relationships at Franklin Point are quite so equitable. With little to constrain its growth here except eradication, nonnative European beachgrass is well entrenched. The species competes with native American dune grass for beachfront property along much of the Pacific coast, and it usually wins. While both are adapted to a harsh life on low-nutrient, windswept coastal sand, reproducing through thick underground rhizomes and airborne seeds, the two grasses are easy to distinguish.

American dune grass (Leymus mollis) grows up to four feet tall in loose and scattered patches that anchor shifting sand and block coastal winds. European beachgrass (Ammophila arenaria) does the same things but better, spreading more aggressively in dense clumps that can cover dunes like a layer of sod. This not only crowds out native species that depend on the pockets of space left by American dune grass, but also alters the topography by creating taller, steeper, less mobile dunes, like miniature mountains among rolling hills.

Ironically, European beachgrass was introduced in the early 1900s for precisely this purpose: to stabilize coastal dunes near roadways and buildings. And while American dune grass is no slouch—it has been employed for wheat breeding and hybridization due to its robustness and high adaptability—the same quality that makes it valuable, an open growth pattern, has also left it vulnerable to habitat loss.

California State Parks is now turning the tables on the invasive European grass by burning it and then applying herbicide to individual plants. Staff scientist Tim Hyland says European beachgrass could be gone from the area in as few as five years, ensuring natives have more space to occupy.

Continuing down the coast along the Atkinson Bluff Trail from Franklin Point, where 270-degree views frame the Pigeon Point Lighthouse to the north and protected beaches of Año Nuevo Point to the south, we soon enter a third habitat: coastal bluff scrub. (Corelli’s book lists nine habitat types, in all, along the immediate San Mateo County coast.)

Poison oak and squat California sagebrush grow here, as well as coyote brush. The notoriously impenetrable landscape fostered by that shrub was long kept at bay here by the Quiroste tribe, who occupied a significant village just east of here and actively managed the land around modern-day Año Nuevo for at least 1,000 years or more. They burned these terraces annually to aid seed collection, ensure good harvests, and keep grasses down for easier hunting.

California State Parks reignited the practice in the 1970s, initially to eradicate an invasive plant called gorse. Today the parks department conducts biennial burns of Cascade Field—a 150-acre parcel bordered on the west by the bluff’s edge and on the east by Highway 1—to conserve what little is left of the coastal grasslands.

Among the plants benefiting are a handful of native bunchgrasses rarely found all in one place along the coast, including purple needlegrass (the California state grass), maritime brome (a perennial related to the invasive yet endearingly named hairy chess), and California oat grass (whose range extends as far inland as the Sierra). Another is tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), a species whose coastal range reaches down from Alaska and peters out around Monterey, not far south of Año Nuevo. The limiting factor is likely temperature: Adapted to cool, moist climates, in Central California this grass relies on fog to maintain an environment more characteristic of its northern and high-altitude distribution. Here, where the Pigeon Point Lighthouse long alerted fogbound ships to the presence of land, is one such place.

Amid the bunchgrasses grow a variety of other plants—more than 200 species in all—including wildflowers that provide an explosion of color April through mid-May. “That grassland has the most spectacular wildflower shows left, at least in the Santa Cruz District of California State Parks,” Hyland says. “You can go out and see acres and acres and acres of wildflowers in a good spring. You don’t see so much of that around here on the coast anymore.”

Beyond conversion to scrub, another way to permanently lose native grassland is to plow it for agriculture, the fate of many prairies along the California coast, Hyland says. “Once you kill a coastal prairie, you never get it back.” Cascade Field and much of the area around Franklin Point has been grazed—first by Spanish and later by Mexican and American ranchers—but never plowed. Grazing has less impact on the seeds in the soil, allowing native plants to persist.

Even with the European beachgrass, the iceplant, the pampas grass, and other nonnatives scattered throughout northern Año Nuevo State Park, these trails offer a vision of what the coast looked like before Europeans arrived, says Michael Vasey, a lecturer in the biology department at San Francisco State University and director of the San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve. “It’s a relatively intact landscape, so it has these natural communities that once characterized the coast and are now not encountered in many places at all, really,” he says. “It’s a historic landscape.”

A broad fire road marks the southern edge of the burn area, toward which coyote brush creeps from the other side, faithful to the laws of succession. This doubles as an exit route for hikers, leading from the cliffs to the parking lot where our second vehicle awaits.

But the hike needn’t end there. The Atkinson Bluff Trail continues south, tracing the cliff’s edge for another mile or so before heading back inland toward the highway via the Cascade Creek Trail spur. At this point the California Coastal Trail technically follows the shoulder of Highway 1. The beaches and bluffs ahead, from Cascade Creek to the Año Nuevo State Park Visitor Center, are closed to the public to protect the park’s year-round resident elephant seals. South of Año Nuevo, the CCT continues, following the shoulder of Highway 1 through the remainder of San Mateo County. It doesn’t return to true trail until Waddell Beach, two miles south of Año Nuevo Bay.

The CCT is a work in progress. The notion of establishing a continuous pedestrian route the length of the state was included in the original legislation that created the California Coastal Commission in 1976, but the CCT didn’t receive a state mandate for completion until 2001.

Two years later, a report ordered by the California State Legislature determined that the project could be completed at a cost of $322 million. That sum accounted for trail construction, right-of-way acquisitions on private land, and highway corridor improvements to safely accommodate an adjacent trail where no other routes exist—though it didn’t come with a timeline. Seventeen million of those hypothetical dollars were designated for San Mateo County.

To date, about 700 miles of trail have been incorporated into the system statewide. Of these, 400 miles have been marked with CCT signs. In rural southern San Mateo County, south of Half Moon Bay, the trail is only about one-third complete and essentially devoid of any official signage. From Half Moon Bay north to Daly City the trail is about two-thirds developed, most of which is signed.

North of Atkinson Bluff and Franklin Point, the CCT continues along a beach before realigning with the shoulder of Highway 1 at the state park border. Here Año Nuevo meets Cloverdale Ranch, a property purchased by the Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) 20 years ago. An inland portion of the 5,638-acre parcel was transferred to nearby Butano State Park in 2000, but the stretch west of the highway remains in POST’s hands and is effectively closed to the public. Most of the bluffs, just inland of where a trail could go, are currently leased to a dry-farming operation growing pumpkins and peas.

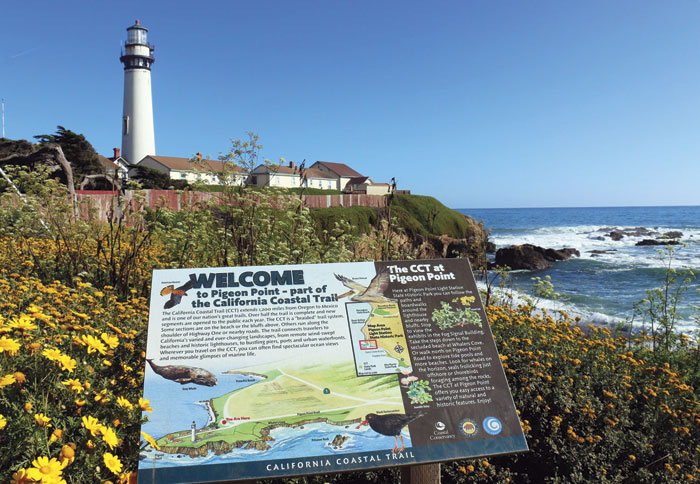

Beyond Cloverdale Ranch, a couple more miles up the coast, is another state park holding at Pigeon Point, where the well-preserved 1871 lighthouse and meandering bluff-top trails (not to mention a youth hostel with outdoor hot tub) draw crowds. Given the allure of this historic and scenic corridor, the state Coastal Conservancy, which leads development of the CCT, is eager to build a connection through Cloverdale Ranch and close a key gap in San Mateo County.

“We’re looking forward to working with POST to evaluate the opportunity to design and eventually construct a trail,” says Tim Duff, who oversees the conservancy’s work on the CCT. “It will be fantastic. It’s a beautiful coastal terrace, and that’s why it’s the highest priority for us to work on the south coast of San Mateo County.”

Seven miles separate the Pigeon Point lighthouse and the Año Nuevo visitor center, where 35,000 people embark on guided walks every winter to see elephant seals during pupping season. Franklin Point and Cascade Field lie in the middle of these destinations, a brief expanse where millennia of human and natural history are still playing out between the road and the shore.